ICONS FROM SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE AND SINAI : YUGOSLAVIA : Icon Painting from the 13th to the 17th Century

Byzantine art spread over Europe, Asia, and Africa for many centuries, but there came a time when its sphere of influence was reduced to no more than the Balkan peninsula. Icon painting had by then a long-established tradition behind it which specified exactly what an icon should be. The looting of Constantinople in 1204 was particularly disastrous for the older works of Byzantine icon painting, and precious examples were either dispersed abroad or destroyed en masse. Thus the student of the history of Byzantine icons must make do, for the most part, with works which had been transplanted to other countries — Russia, Sinai, Georgia, or the West — at some early date. So few of the icons that were made in Constantinople or the Greek islands before the thirteenth century have survived that it is not possible to trace the course of art in them before that time. Only in recent decades has the evolution of the Byzantine icon between the sixth and thirteenth centuries become somewhat clearer, thanks to the unique collection discovered in the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Sinai.

For too long there was a deep-rooted misconception that the icons of Byzantium, and of the regions under its artistic influence, were rigidly stereotyped by the heavy hand of tradition. Recent research has demonstrated exactly the contrary; that, in fact, the icon was often chosen as the means of launching new ideas in art. With this new insight, the history of the icon has become steadily more fascinating during the past few years. Perhaps this book, in its attempt to give an over-all view of icons in the Balkans, will demonstrate that icons of the later period must be subjected to historical analysis if light is to be thrown on the many-sided complexity of the art — for during the Middle Ages and throughout the centuries of Turkish rule it spread seemingly without hindrance across the frontiers separating one region from another.

Byzantine historians of the early thirteenth century describe in detail the tragic fate of the works of art plundered in Constantinople. The great lament "De signis constantinopolitanis," by Nicetas Choniates, is almost a funeral oration for the old art of the great center. But recent studies on the origins of the Palaeologue renaissance have made the later art of Byzantium appear in a quite different light; indeed, this last metamorphosis of Byzantine art now seems to have been the latest but most beautiful gift of liberated Constantinople to Europe. It may well be that only in the realm of art could a state that was exhausted in strategy and economics still manifest its magnificent maturity.

In old eulogies addressed to Constantinople, one encounters the poetic idea that the young New Rome was the state "embraced by both land and sea," the outstretched hand of Europe "kissed by the waves of Asia." It is true that Constantinople received from the East in the thirteenth century the final impulse for the transformation of its art, from Asia Minor and especially from Nicaea where the Emperor had taken refuge. Around the middle of that century, the art of that region, monumental and epic in its sweep, broadly and clearly conceived, became the model for the art to be produced by the younger peoples of the Balkans.

In the first decades of the thirteenth century, Serbia had become a kingdom with an autonomous church under its own head. Although the young Nemanja dynasty staunchly rejected the authority of Byzantium, it was precisely in those years, when it was shaking off the political control of Constantinople, that it most closely joined hands with Byzantine culture. Saint Sava, the founder of the independent Serbian church, expelled the Greek bishops from their sees on Serbian territory, yet his ties to the Orthodox Church remained unshaken. Together with his father, he founded a Serbian monastery on Mount Athos and induced artists from Constantinople to emigrate to a Serbia that was still in the Dark Ages. Under the Nemanjas Serbian art took on new life. Thereafter it continued to flourish without interruption, within the framework of Byzantine art as a whole, until the fall of Smederevo in 1459 — and, indeed, until well into the seventeenth century in spite of Turkish domination. Closely linked to Byzantine and so-called post-Byzantine art, early Serbian painting never abandoned the principles of Eastern Christian conceptions. A comparison of the Greco-Byzantine, Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Serbian icons reproduced in this book will show most effectively what qualities they had in common and what was peculiar to each of them.

The icon has many features distinguishing it from other branches of painting. It is neither fixed permanently to a wall nor, like miniatures, associated with a text in some particular language; therefore, it is both portable and easily copied. New ideas and outstanding achievements of master painters were quickly disseminated by means of their icons. Thus an icon by a great master, when brought into a culturally provincial region, inevitably exerted extraordinary fascination and was soon adopted as a model for others. In early Serbian art, icons were done by Greek painters for the most part; they were the more esteemed for that, but they also bring out the contrasts between the Greek and the native conceptions. This contrast between foreign and native products helps us to pin down the complex, often barely discernible peculiarities of the regional art. Yet it would be naive and anachronistic to try to reconstruct some sort of medieval national style emerging from a conscious opposition to Byzantine models. Whatever was specifically Slavic was manifested more spontaneously and, for that reason, is more precious. There are the merest forebodings of such a style in the epic sweep of its treatment of subject matter, and a certain fierceness of temperament in its insistence on what was already an individual cultural tradition. A tenuous but nonetheless distinct notion of what constitutes physical beauty was also carried over from the real world onto the gilded surfaces of icons. In a development that covered centuries, these individual traits coalesced, ripening into a specific mode of artistic expression that, particularly in early Serbian painting, brought about a mutually dependent relationship between icon painting and fresco painting. This, in turn, was to lead to new artistic phenomena of even greater significance.

The close relationship between icons and frescoes is evident in the art of Ohrid as early as the eleventh century. Although not a single icon from that time is still extant, their appearance and style are known to us from the imitations of them, painted in fresco, in the altar area of the Church of Saint Sophia in Ohrid. Naturally enough, these imitations include only those iconic features easily reproducible in fresco technique. The icons in beaten silver cases that are listed in the inventory of the Monastery of the Merciful Mother of God near Strumica must certainly have been executed in a far more subtle technique, and have had a quite different appearance.

In the eleventh century, it was the urban centers of the Balkans which particularly favored Byzantine icons. The Imperial protospatharius Ban Stephen presented five icons, one in silver, to the Church of Saint Chrysogonus in Zadar on the shores of the Adriatic in 1042. Certain cathedrals, in cities which are still the seats of bishoprics, contain very old, so-called wonder-working icons that have been preserved through the ages because they were thought to protect the faithful against dangers. The cathedral in Skopje, for one, takes its name from the wonder-working icon of the Three-handed Mother of God that has been kept there. It seems that already in the eleventh century, and certainly from the twelfth onward, the Archbishopric of Ohrid was an important artistic center, but where its influence did not extend, icons were not so much in use. From the biographies of the first members of the Nemanja dynasty, one learns that icons were even deliberately discarded in Serbia during the twelfth century, under the prompting of the heretic sect of Bogomils. As soon as Saint Sava was made archbishop, he particularly stressed in his sermons that icons ought to be revered, asserting that gazing on icons "raises the eye of the spirit aloft to the original of the holy personage therein portrayed." Expressing his devotion to the cult of icons, Saint Sava thundered against "those who cast aside the holy icons and who neither paint them nor bow down before them." When the young dynasty was finally won over to Byzantine Orthodoxy, it placed special emphasis on the icon; even during the lifetime of Stefan Nemanja, Saint Sava, who was Stefan's son and biographer, stressed that the venerable founder of the dynasty had endowed the monastery of Studenica with "icons and liturgical vessels .. . books and vestments and draperies." It is known that the monastery of Žiča received gifts of icons from Saint Sava and from Stefan the First-Crowned. Later the historian Danilo, in his

Lives of Kings and Archbishops, pointed out again and again that the founders of monasteries presented them with "icons in splendid beaten gold and adorned with choicest pearls and precious stones, along with many relics of saints." Danilo singled out Queen Helena for particular praise because she endowed the monastery of Gradac with icons, and King Milutin for his gifts of richly worked icons to the Monastery of the Virgin in Treskavac.

Even the earliest Serbian texts from the thirteenth century give detailed descriptions of these icons. Theodosius, the biographer of Saint Sava, recounts how the saint commissioned two "standing" — that is, full-length — icons of Christ and the Virgin from "the most skillful painters" of Salonica, as gifts for the Monastery of Philokalas in that city. He adds that one of these icons shows the Virgin of the Mountain, so called because of the vision of the prophet Daniel. We even learn how the icons were ornamented; the saint had them both adorned with "gold wreaths, precious gems, and pearls."

The beginnings of icon painting in Serbia, in a milieu as yet without its own artistic tradition, can scarcely be determined from the very few icons that survive from the late twelfth and the first half of the thirteenth century.

ODEGITRIA VIRGIN. End of 12th or beginning of 13th century. Mosaic. Museum, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos

The earliest icon from a Serbian monastery is at Chilandar, a Virgin in mosaic of the Odegitria type dating from the late twelfth century. The work is still closely tied to monumental wall mosaics and fashioned from rather large stones. Its style is close to Venetian-Byzantine work and was probably made on the Adriatic coast, perhaps in Dalmatia; it made its way to Mount Athos, perhaps as a gift from Saint Simeon Nemanja, the founder of the new Monastery of Chilandar.

In the mausoleum of Stefan Nemanja at Studenica, the frescoes dating from the early thirteenth century include two imitation icons which give us some idea of the appearance and style of Serbian icons at that time. On one fresco, now badly faded, an old icon of Studenica with the Virgin Kyriotissa can be made out; this icon was itself an imitation of an icon in the Monastery of the Virgin Kyriotissa in Constantinople.

The other fresco, in good condition, depicts the transporting of the bones of Nemanja from Athos to Studenica, and includes a carefully executed copy of an old icon of the Virgin Paraklesis. This image, though part of a narrative fresco, repeats a type whose iconography was already well fixed and often copied, although its style already reflects considerable deviation from the Byzantine prototypes; the face of the Virgin is characteristically Slavic. The rather simplified drawing and bright clear colors lend the painting a lyrical and intimate note that is quite alien to icons originating in Constantinople and Salonica.

Icons that portray with a certain measure of freshness and freedom the motherhood of the Virgin and the infancy of Christ were especially popular. The miniatures of a thirteenth-century illuminated Gospel from Prizren, destroyed by fire during the bombardment

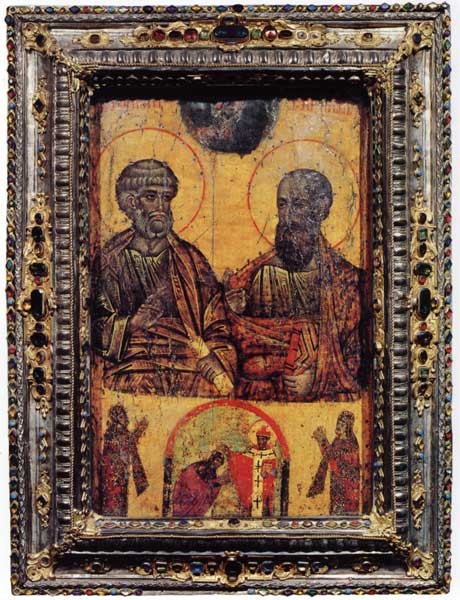

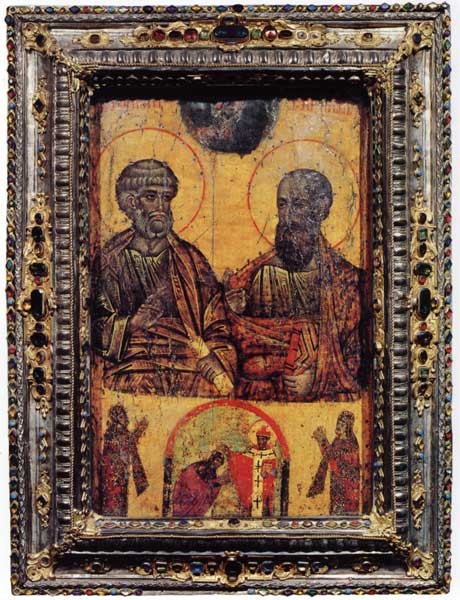

of Belgrade in 1941, included two which were, in essence, naive copies of icons. One represents an attempt to copy an icon of the Virgin of Pelagonia, the other an icon of the Virgin of Consolation. Some idea of the intimate lyrical quality of Serbian icons of the first half of the thirteenth century can also be gleaned from the writings of the time, indirect as such evidence must be. Thus, the archives of Dubrovnik contain a document deposited there in 1281 by Queen Beloslava, consort of King Vladislav who, around 1235, had founded the Monastery of Mileševa. This document is an inventory of the family collection of icons; it is the first known catalogue of such a collection in Serbia, and full of valuable information. Of the twenty-one icons, two were reliquaries, one was a portrait of King Vladislav, four were of Christ and an equal number were of His Mother, two showed the apostles Peter and Paul, and others showed popular saints — Nicholas, John the Baptist, George, and Theodore — as well as one of the Archangel Michael. There was one family portrait, an icon of the founder of the dynasty, Saint Simeon Nemanja; this was richly encased in silver — "cum argento et cum septem petris de cristallo." It is interesting that one of the icons of the Virgin is described as being made of bone — "de osse." The remaining icons have no indication of their subjects. One icon contains an interesting suggestion of the general character of the collection: the inventory remarks that it represents "Christus sicut dormivit", in other words, an

imago pietatis, a Christ as Man of Sorrows. This subject, lyrical and at the same time dramatic, was often used in early Serbian painting.

The expulsion of the Latins from Constantinople in 1262 and the advent of the Palaeologue dynasty exerted a strong influence over the development of art in the Balkan interior. In those years, the last great flowering of art began in Constantinople. The Palaeologue renaissance, whose initial phase was marked by a monumental classical style with broad forms and bright colors, is best known through the frescoes in Sopoćani and a group of illuminated manuscripts that are not yet definitely dated. We can only guess at what icons must have looked like in the new, clear, classical style of the mid-thirteenth century since none has been preserved. There may be a hint, however, in the standing figures in the first, lowest tier of figures in the Sopoćani frescoes. It is only in the sixties of the thirteenth century that the history of icon painting in Serbia and Macedonia becomes clearer, for some icons have survived from that time and certain of them are even dated and signed. In 1262—63, Archbishop Constantine Kabasilas of Ohrid presented to a church in that city a large icon of Christ which has come down to us in good state, even to the dedicatory inscription on the back. Another signed and dated icon is the damaged and as yet unrestored Saint George from Struga. The original inscription on the back is from 1266—67 and identifies the donor, John the Deacon, and the artist, named John, who described himself as a "historiographer."

It seems that as early as the beginning of the thirteenth century, the better icon painters acquired enough fame to be known by their names. A devout pilgrim, Anthony of Novgorod, remarked in his description of Saint Sophia in Constantinople, about 1200, that a certain "skillful Paul" had in his time painted the Baptism of Christ in the baptistery. In the collection of the Serbian Monastery of Chilandar, on Mount Athos, there is an extraordinary icon of the head of Christ which must have been done by one of the leading painters of the second half of the thirteenth century.

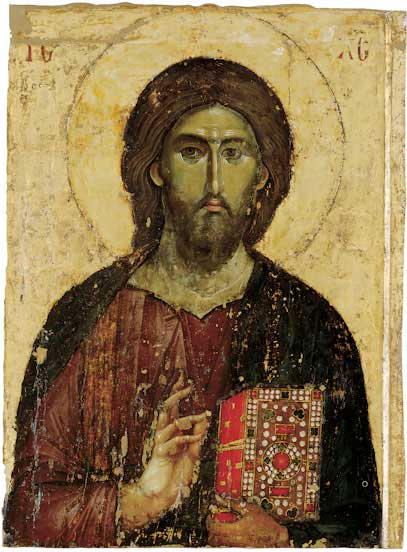

HEAD OF CHRIST THE REDEEMER. 13th century. Museum, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos

It is very close in style to the fresco in the cupola of the Church of the Apostles in Peć, painted no more than a decade earlier. Somewhat harder and less consistent, but otherwise very impressive, is the icon from Ohrid with the Odegitria Virgin on the front face and the Crucifixion on the back. The hard drawing and strikingly sculpturesque modeling, and the expressiveness of the Virgin at the foot of the Cross, anticipate the dramatic so-called First Style of Michael and Eutychios, the well-known painters of Ohrid. The finest and certainly the most artistically significant icon from Ohrid of the late thirteenth century is a large image of the Evangelist Matthew.

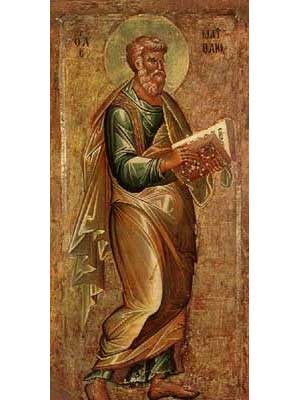

THE EVANGELIST MATTHEW. End of 13th or beginning of 14th century. National Museum, Ohrid

Done shortly before 1300, it was strongly inspired by the classical Byzantine style of the tenth century. In style and iconography it closely resembles the full-length figure of the evangelist in a manuscript (Cod. Theol. gr. 240) in the National Library in Vienna.

The stylistic development of icon painting in some parts of Macedonia, for example in Ohrid, at the end of the thirteenth century, ran parallel to that of the better-known monumental wall paintings. It proceeded from the relatively dry calligraphy of the Christ of Archbishop Kabasilas, through the dramatic Crucifixion, to the classicism of the Evangelist Matthew. This was a single continuous phase that corresponds to the steps in the development of the contemporary frescoes in Manastir, Macedonia; these began with the First Style of Michael and Eutychios, in the Church of the Peribleptos in Ohrid, and ended with the classicism of the frescoes in the Church of Saint Nicetas and in Staro Nagoričino.

In Serbia, icon painting was exposed to influence from the east and the southwest. The proximity of the region to the Adriatic coast, with its Romanesque-Byzantine provincial art, is most obvious in thirteenth-century Serbian miniatures; in these, Romanesque ornamental initials remained in vogue right up to the end of the century. There is a similar influence to be seen in the sculpture of the time. In painting, Romanesque elements persisted in mural art up to 1240, disappearing only later. Evidence of the powerful impact of the West on Serbian icon painting in the second half of the thirteenth century is conspicuous in a fresco copy of an icon in the Cathedral of Prizren, and in a late thirteenth-century Serbian icon belonging to the Treasury of Saint Peter's in Rome. The painted copy in Prizren Cathedral is in the lowest tier of frescoes, dating from around 1270; it depicts Christ the Nourisher, in markedly stylized, expressive drawing that much resembles the style of Florentine madonnas from those years. The icon in Saint Peter's has come to the attention of scholars largely through W. F. Volbach's efforts; even in its over-all appearance one is immediately struck by the absence of Byzantine formal conceptions.

Treasury of Saint Peter's in Rome, Kings Dragutin and Milutin, their mother Queen Helena, and a sainted bishop blessing the queen, late XIII century

It is divided horizontally into two areas, the upper one larger, the lower narrow and elongated, and in this respect it resembles Western votive pictures. It may originally have belonged to a series of similar icons that were sent to Rome by Serbian rulers. Of special interest is the lower area on which are portrayed the Kings Dragutin and Milutin, their mother Queen Helena, and a sainted bishop blessing the queen. In style this icon is closely related to a thirteenth-century icon from Sinai which Sotiriou, with much probability, attributes to some Apulian workshop.

Our icon of Saints Peter and Paul itself, now in Rome, probably originated in a workshop in Kotor, the principal Serbian port on the Adriatic. It was a thriving art center in the thirteenth century, sending forth goldsmiths, painters, architects, and sculptors, most of them to work in the interior. The art of Kotor, like that of the nearby towns Bar, Skutari, and Dubrovnik, was at the time closely linked to Apulia in Italy, on the opposite shore of the sea. Be this as it may, the Vatican icon has much in common with the other products of Serbian art in the thirteenth century. The icons that have survived from that century clearly show that Serbian painting of the time was far from uniform, either in style or in quality. Written sources permit us to conclude that in mid-century the icon was the most prized form of painting; it may be that the special reverence paid to icons in medieval Serbia came about through opposition to the heretical notions of the Bogomil sect. It remains true, however, that in Byzantine art as a whole the icon was at that time steadily assuming a more prominent place in the activity of painters and was in ever greater demand as an important element for the decoration of church interiors.

With the new classicism of the mature Palaeologue style, the feeling for broad surfaces and monumental expression becomes lost, in favor of a more intimate, miniature-like precision. There was a general predilection for a reduced format and a concentration on pictorial values. This explains why the fourteenth-century icon was increasingly awarded a place of honor in the system of painted decoration. In accord with the general trend throughout Europe, painting on separate wooden panels began to predominate in Serbia as early as 1300. Slowly but surely, the iconostasis developed into a wall completely covered by panel paintings which not only appropriated the finest themes from mural art but ended by exerting a disastrous influence on that art. Little by little, mural painting came to be no more than a discreet accompaniment, a mere echo of what was so solemnly and impressively presented in the icons that were set up with maximum effectiveness on the iconostasis, where they could be seen and admired by everyone.

In the Balkans, the transformation of the stone altar screen into a true iconostasis was long and slow. From the late thirteenth until the late seventeenth century, the changes in the iconostasis had a marked influence on icon painting and on the development and use of the various types of icons. Finally, there came to be a vast range of icons — from the icons representing the feasts of the church and those used for processions or calendars, down to the imitations of entire iconostases in miniature and to small amulet and reliquary icons.

Until the end of the thirteenth century, the altar screen in Byzantine churches was part of the stone decoration and its form scarcely differed from that used in early Christian basilicas. But after the defeat of the Iconoclasts, painted decorations became a permanent feature. As a rule, large icons with full-length figures were hung on the masonry pillars — the steloi — on either side of the center of the screen, and the upper parts of the icons were ornamented with carved frames of stone or stucco. The common idea that icons were "returned" to the pillars at that time is based on the supposition that before the Iconoclast controversy, these monumental icons had normally been placed on the iconostasis. But the earliest surviving specimens indicate that this type of screen with large icons was not known before the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. All the elements needed to reconstruct the original stone screen in the Church of Saint Sophia in Ohrid — even the two icons — have been preserved, but, unfortunately, the church was converted into a mosque and they were then incorporated into the floor of the altar area and the "mimbar," the Moslem pulpit. However, the twelfth-century altar screen in the Church of Saint Panteleimon in Nerezi has survived almost intact.

This transitional form, between an altar screen and an iconostasis, lasted in Serbian and Macedonian regions until the first years of the fourteenth century. Its basic components consisted of screen slabs that enclosed the chancel, small columns, an architrave, and large icons to either side of the doors. The spaces between the columns were left open, and curtains were drawn across them only when the liturgy required it. Near the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth century, the custom of introducing icons into the spaces between the columns was initiated. This meant that those icons which had formerly been hung high on the columns were now lowered almost to floor level. Instead of portraying full-length figures they now showed half-length figures; but below them hung sumptuous textiles that gave the impression that the figures were standing behind curtains which concealed them below the waist.

The iconostasis of 1317 from Staro Nagoričino gives us an idea of how, in the interior of the Balkan peninsula, the altar screen was transformed into the iconostasis, with only minor changes. It is complete down to the last detail, although the icons themselves and the drapery below them were imitated in fresco. While the evolution of the iconostasis in the Balkan countries certainly had its own peculiarities and perhaps its late forms as well, it can be followed in detail in the surviving examples. Precisely for this reason, the early iconostases of medieval Serbia have greater significance for us today than merely local and provincial monuments. The innovation of placing the icons in the spaces between the columns of the stone screen led to the creation of a special type of large icon that required an appropriate, firmly established format and a new character. Lowered from its former high position and brought closer to the worshipers, the icon underwent considerable change. The earlier icons of full-length figures, permanently fixed high up, were in essence not very different from frescoes: immobile and lofty as murals, these icons shared their

monumental character with murals in many respects. When, however, they were set lower between the columns, the new icons were on an equal footing, so to speak, with those who revered and kissed them; brought close to the eyes and lips of the believers, the images themselves became more human. To remove them somewhat from the sphere of mortals they were provided with lavish frames; and just as the images were painted to be seen from close by, the frames were executed with precision, carved finely so that attentive worshipers would be led to marvel at their painstaking perfection. Once the large icons were transplanted into the spaces between the columns, they no longer needed to be of monumental size and fixed in place. The older icons were thought to be protectors in time of public need, and according to the monastic rules they were never to be taken down except in the event of fire or earthquake. But by the fourteenth century, the large icons were even taken outdoors on the occasion of great feasts, and special notches and recesses were carved into the lower part of the frames to facilitate their being carried about — as we know from later Russian examples. Most of these icons of the Balkan Slavs were painted on both front and back in accord with fixed liturgical prescriptions. At the start of the fourteenth century, the large ceremonial icons continued to repeat the time-honored iconographic themes but motifs of a significantly more intimate character began to appear. The very names given to these new icons tell us that they originated in Constantinople.

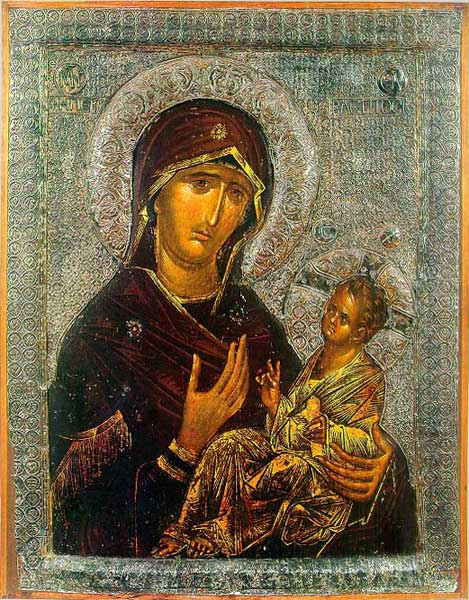

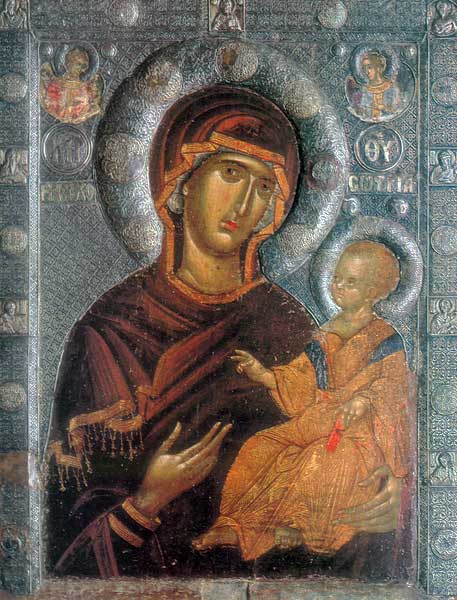

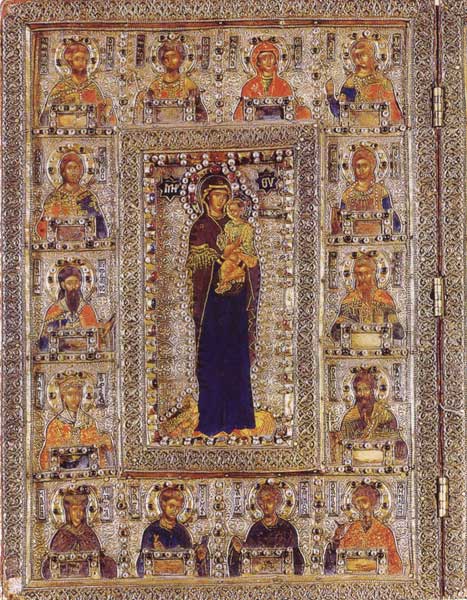

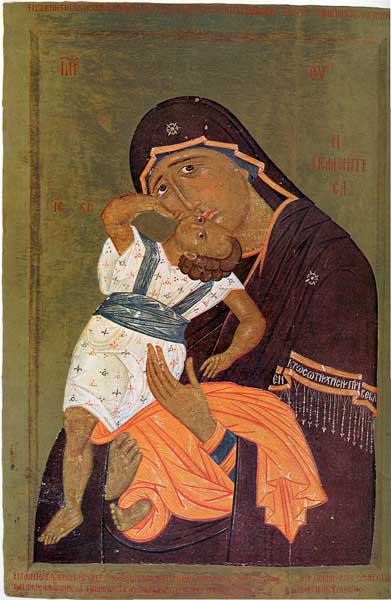

From the church of the Mother of God Peribleptos (St. Clement’s), Ohrid, The Mother of God Peribleptos, 14th century

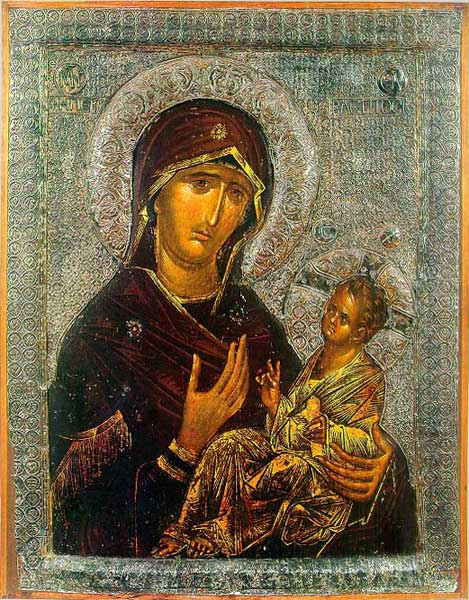

The well-preserved, silver-encased icon of the Peribleptos Virgin, from the church of the same name in Ohrid, is probably a copy of a Constantinopolitan prototype, the wonder-working icon in the Monastery of the Peribleptos Virgin which was built in the eleventh century but enjoyed special fame from the start of the thirteenth century up to the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

In the Ohrid icon the characteristic traits of the Palaeologue renaissance are well in evidence: the classical forms of the figure of the Virgin, the restrained coloring, the emphasis on feeling. The new intimate relationship between the Mother and Child becomes especially striking when one compares this icon with older variants of the same type which basically conform to the iconographic model of the Odegitria Virgin. Originally painted on one side only, the reverse was painted with the Purification of Mary much later in the fourteenth century.

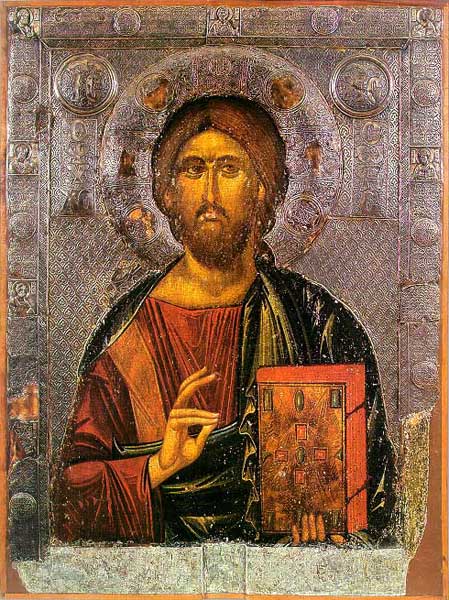

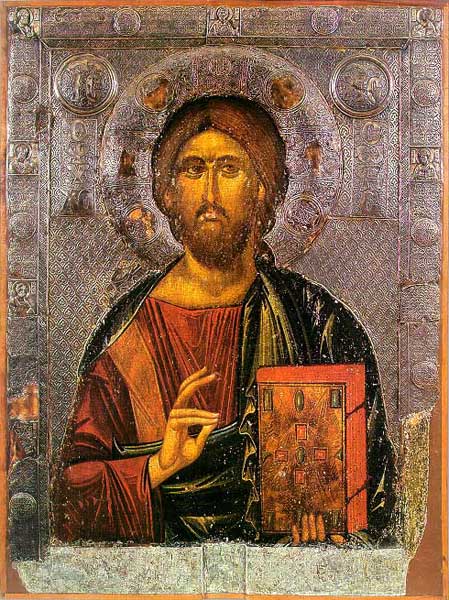

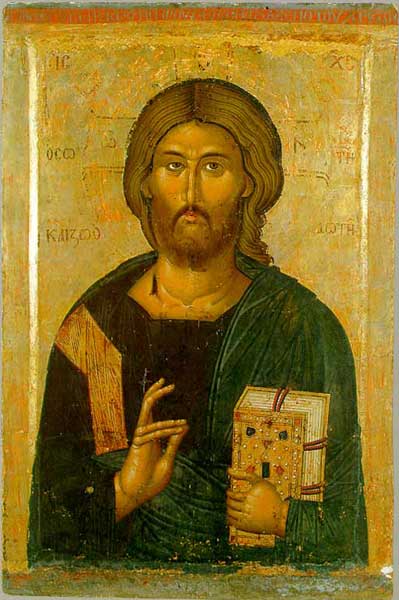

From the Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos (St. Clement’s), Ohrid, Jesus Christ Soul Saviour, Processional icon. (On reverse, - "The Crucifixion".), 14th century. Today - at the Icon Gallery, Ohrid.

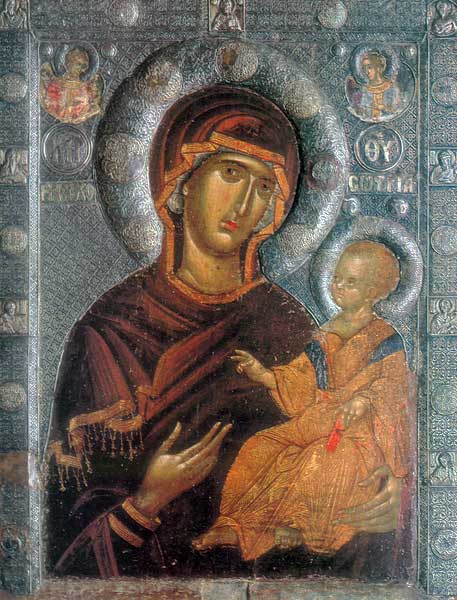

The monumental pair of icons in Ohrid showing respectively Christ and the Virgin as Saviours of Souls date from the transitional years between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; they rank among the finest icons of Ohrid and, indeed, of all of Byzantine art. Both are double-faced: on the back of the icon of Christ is the Crucifixion; on that of the Virgin, the justly famous Annunciation that has recently been restored. The front paintings on each icon retain the hieratic character of their earlier iconographic prototypes, although it is discreetly toned down.

VIRGIN THE SAVIOUR OF SOULS. Beginning of 14th century. Double-faced icon, one of a pair, National Museum, Ohrid

In the icon of the Virgin the pose is shifted from the traditional frontal axis, and there is a more intimate relationship between the Mother and Child. While the painter's approach remains severe, with muted colors and powerful modeling, an element of refinement in harmony with the basic conception is introduced by the lavishly embossed silver background. The harmony between silver and paint is particularly successful in the icon of the Virgin, whereas in that of Christ extensive repainting in the sixteenth or seventeenth century has left only the forceful head relatively unaltered.

The images on the back faces — the Annunciation and the Crucifixion — unlike those on the front, are probably each by a different artist; the one responsible for the Annunciation was beyond doubt the more significant.

ANNUNCIATION. Beginning of 14th century. Double-faced icon, one of a pair, National Museum, Ohrid

A large number of fourteenth-century Byzantine icons of the Annunciation have come down to us but the example from Ohrid holds a special place among them for its purely artistic qualities, not only for its format and excellent state of preservation. All the beauty of the early style of the Palaeologue renaissance seems concentrated on the golden surface of this icon. The thoroughly calculated impression of depth, the modeling of the figures, the contrast between movement and repose — all was carefully designed and rendered with masterly assurance, with no trace of the usual soft sentimentality which, in later Palaeologue painting, ended in pantomimic gesture, cloying sweetness, and a certain lukewarm indifference. The master who painted the Annunciation cultivated a dramatic style with solid forms and strong colors. But his art was not without defects: a glance at the stiff position of the Virgin's left hand suffices to reveal his uncertainty as a draftsman; nor could he create an over-all atmosphere which would unite figures and action into a whole.

CRUCIFIXION. Beginning of 14th century. Double-faced icon, one of a pair. National Museum, Ohrid

The artist who did the Crucifixion, however, achieved a most convincing general mood. Conventional as his drawing and composition are, he nevertheless combines his feeling for darkly portentous lyricism and deep-felt poignancy into a whole by his use of softly modeled forms and refined coloring. The Annunciation and the Crucifixion, from the same year and in the same style, show how similar conceptions, when realized by quite different personalities, ended in marked divergencies — and this in an art that, especially in the first decades of the fourteenth century, was striving toward unity of style.

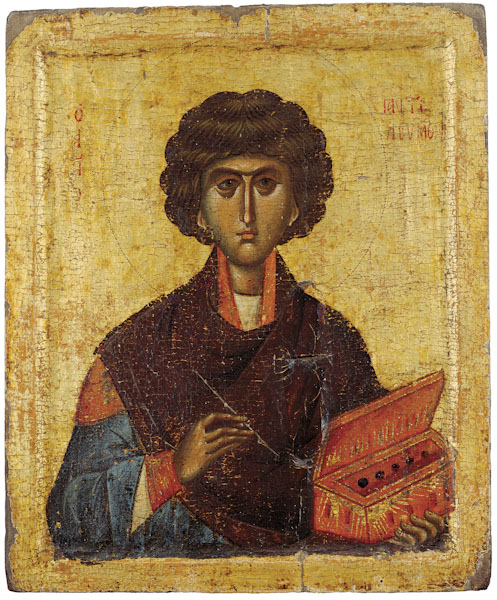

It was difficult to apply the new artistic outlook of the Palaeologue renaissance to the large monumentally conceived icons; these, as fixtures in the liturgy, resisted any deviation from the venerable iconographic formulas. More vigorous and imaginative solutions were found for smaller icons, unless they were mere reduced copies of more imposing works, as is true of the finely painted Saint Panteleimon from Chilandar.

SAINT PANTELEIMON. Beginning of 14th century, Museum, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos

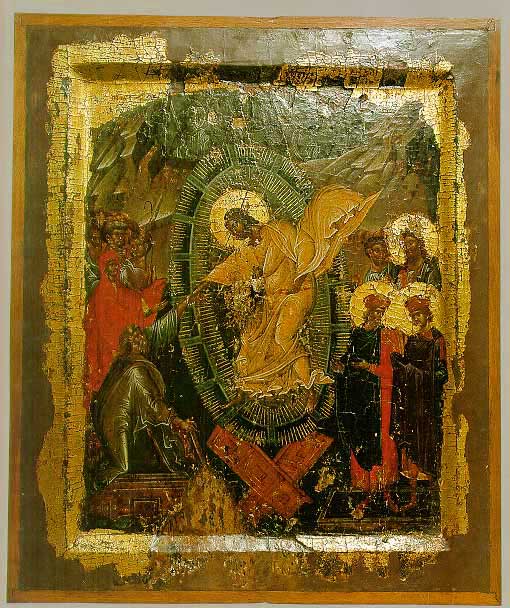

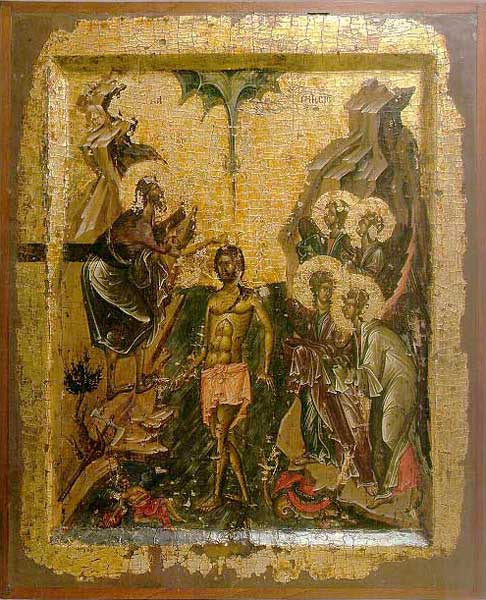

Otherwise, most of the small icons of the first half of the fourteenth century adhered to the new trend in painting which was overtly classicist. In recent years a series of small icons found in Ohrid — no more than eighteen by fifteen inches — has been restored: the icons belong, beyond doubt, to the first half of the fourteenth century and they include a badly damaged Nativity, and a Baptism, Crucifixion, Descent into Limbo, and Incredulity of Thomas.

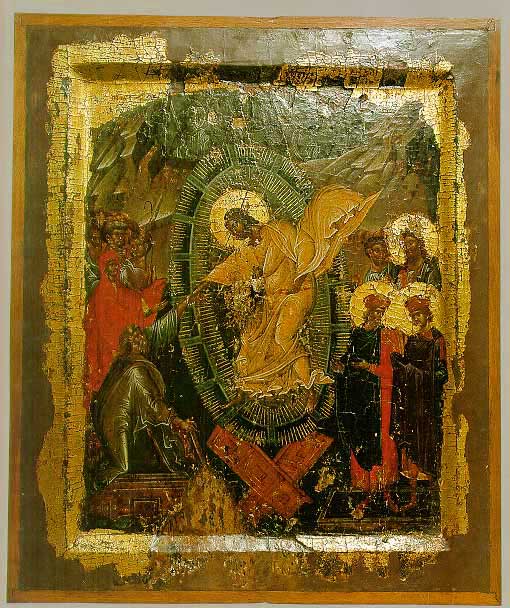

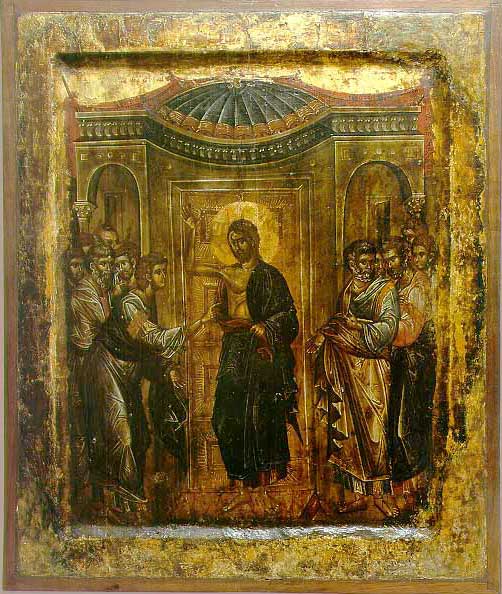

From the Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos (St. Clement’s), Ohrid, Descent Into Hell, Michael and Eutychios icon-painters, 1295 - 1317, Today - at the Icon Gallery, Ohrid.

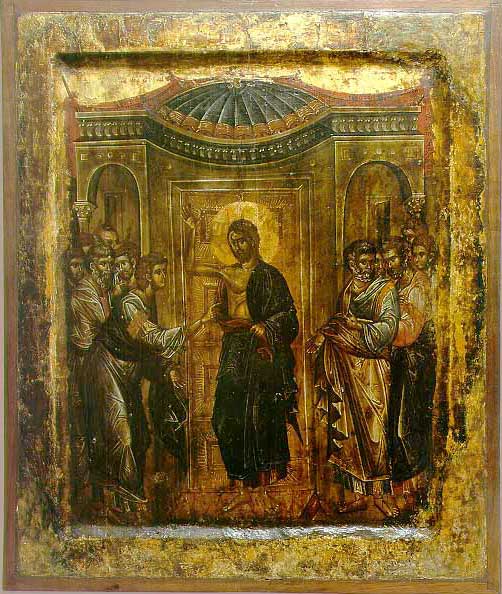

They were all produced by the same workshop, but were based on different prototypes. The Incredulity of Thomas belongs to the severe early classical style and has much in common with the large icon of Saint Matthew. Its composition clings to formulas that had long been traditional and are often found on sarcophagus reliefs. Extremely symmetrical and static in form and subdued in color, it differs considerably from the more attractive and lively icons of the Baptism and Descent into Limbo. These were painted by the same artist, and their agitated drawing, powerfully modeled forms, and intense color represent an early variant of the Palaeologue style that we might call "romantic," which sprang up in Serbia between 1314 and 1320. The same traits are found in the extraordinary frescoes in the royal churches of Studenica and Gračanica.

From the Church of the Mother of God Peribleptos (St. Clement’s), Ohrid, Doubting Thomas, Michael and Eutychios icon-painters, 1295 - 1317

In addition to the powerful influence of Constantinople on Serbian icon painting in the first decades of the fourteenth century, other tendencies can be discerned that were faithful to the native tradition. A rather badly damaged icon of the Purification, signed in Serbian but from Chilandar, shows very clearly how Serbian artists adapted and modified Palaeologue classicism. Firmly bound to tradition, their manner of drawing relied more directly on a severe linearity similar to that of the late Comnenian period. Proportions, drapery, and figures were appropriated from the new art of Constantinople but there is an overtly realistic drive in the handling of movement and emotional expression. The fragment that includes the maidens escorting the Virgin is fortunately better preserved and perfectly reveals the Serbian variant of the early classicism of Constantinople

MAIDENS ESCORTING THE VIRGIN. Detail from PURIFICATION OF THE VIRGIN. 14th century. Museum, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos

In this art of freely combined elements, traditionalism and realism are brought into a happy synthesis with the contemporary trend toward the imitation of antiquity. As interpreted by this master, the group of maidens lost the rigorous and clear-cut rhythm typical of bas-reliefs but, at the same time, it gained a conviction which comes from more realistic, fresher pictorial expression. Similar linear elements and realistic figures are found in the icons on the Dečani iconostasis, about 1350. Following the earlier practice, icons with full-length figures were placed in the spaces between the columns. This is a mid-fourteenth century iconostasis in all its precious entirety with well-preserved images of the Virgin, Saint John, Saint Nicholas, and an archangel, a panel in poor condition showing Christ.

SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST, C. 1350. From the iconostasis, Monastery of Dečani

OUR LADY OF MERCY, C. 1350. Detail. From the iconostasis. Dimensions of entire icon, 64x22 in. Monastery of Dečani

The painters of these icons came to the interior of Serbia from the coastal town of Kotor, whose archives still contain important information about the Greek painters who fostered the "Greek" style of art along the seaboard. The identity of style in these icons and the vast gallery of frescoes in Dečani was recognized long ago, and a comparison between them tells us much about the icons as works of art. Although the signatures in Dečani are in Serbian as a rule, the mistakes in orthography show that at least some of the artists were not familiar with the language. The most likely assumption is that the founders of the workshops in Kotor were Greek but that they had, in compliance with the laws of the town, taken on local youths as assistants and apprentices. We know that this caused the art of the Greek masters in Venice and Dubrovnik to become, in its turn, permeated with native qualities, and it was apparently the case in Kotor, too, for there were workshops and masters in Kotor prior to those in Dubrovnik, and of greater distinction. The only artist who signed his name on the frescoes in Dečani was a certain Srdj (Sergius), but he did none of the paintings on the iconostasis. The style of the anonymous master who did the icons is so close in character to the uncomplicated, bright, fresh manner of painting which was non-Greek in origin that we can be sure that he was a local artist. Although the artists of Kotor belonged to the westernmost regions reached by Byzantine influence, they were acquainted with what was being done in Constantinople in their time. Actually the icon of the Eleousa Virgin in Dečani is, in its iconography, an exact copy of the fresco (recently restored) in the parecclesion of the Church of Chora (Kariye Cami) in Constantinople; every gesture of its prototype is repeated, but they are reinterpreted according to its own style. The Constantinople fresco is meticulously painted in muted colors with the subtlest color variations throughout, whereas the Dečani icon, also the work of a fresco artist, is rich in contrast, clearly composed, and never gives in to naivete. The Dečani master remained faithful to the unchanging qualities of Serbian art, its intense color and vigorously beautiful forms, and did not seek inspiration from figures on classical marble reliefs.

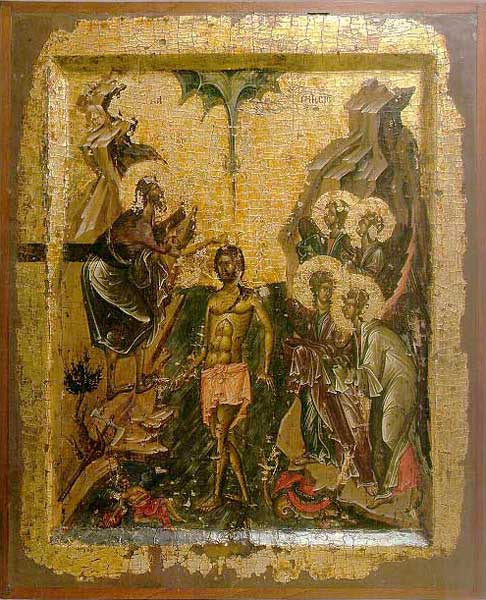

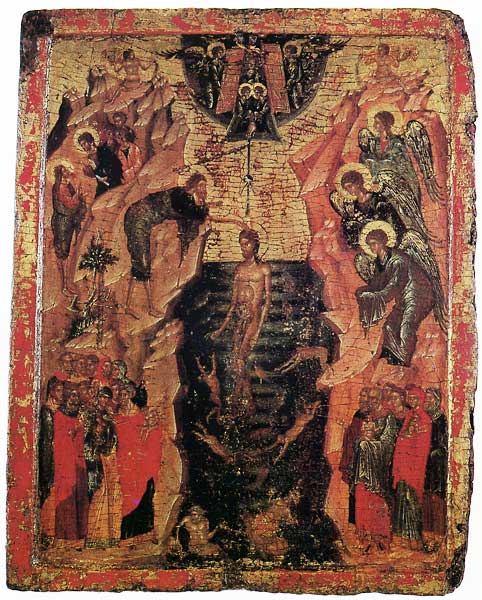

BAPTISM OF CHRIST. 14th century. National Museum, Belgrade

All the refinement of mid-fourteenth-century Byzantine painting is revealed in an icon of the Baptism of Christ, now in the National Museum of Belgrade. It is a masterwork of the mature style of icon painting of the Palaeologue renaissance both for its richness of symbolic and intellectual content and for its virtuosity in manipulating pictural form. A comparison with the Ohrid Baptism clearly reveals what took place between 1300 and 1350: together with a certain agitation in the painting technique itself, the Ohrid icon — classical and romantic at the same time — also has the clarity and symmetry of a work of classical antiquity.

The Baptism of Christ, Michael and Eutychios icon-painters, 1295 - 1317. Today - at the Icon Gallery, Ohrid.

The Belgrade Baptism, on the other hand, is complex in content and overcrowded with figures, but it is also narrative — symbol and vision are one. The composition is vertical and has the format typical of ceremonial frescoes painted on vaults, as, for example, in Staro Nagoričino. The valley of the Jordan is transformed into a rocky canyon crammed with figures, all playing a part in the interpretation of the broad subject matter. Toward the end of the thirteenth century, such depictions of the Baptism accompanied by illustrations of accessory events appeared in fresco painting in Constantinople. Anthony of Novgorod reported, about 1200, that the painter Paul had portrayed the Baptism of Christ with secondary scenes in the great baptistery of Saint Sophia in Constantinople, where catechumens were baptized with solemn ceremony on Epiphany and on Saturday of Holy Week. The Belgrade icon belongs to this iconographic type. On the left side, we see the meeting of Christ and John, and John's parable of the tree and the axe. According to Anthony of Novgorod, the Constantinople Baptism showed "how John instructed the folk and how young children and adults leapt into the Jordan."

The principal scene, the Baptism itself, is based more upon the Epiphany trope of the Orthodox liturgy than on the words of the Gospel. John lays his hand reverently on Jesus' head, and three angels — symbolic of the Trinity — bow toward Him. Directly above the central group, two angels open the Gates of Paradise to reveal Christ as Emmanuel

the Son, in accordance with a verse of the trope. Below this image, two smaller angels bow above the hand of God the Father from which the Holy Ghost, in the shape of a dove, takes flight. On the mountain peaks, which "skipped like rams, and the little hills like lambs" (Psalm 114:4), sit almost nude personifications of Jor and Dan pouring waters from their great vessels into the Jordan. In the stream below, Jordan and the sea are personified, with animated gestures in accordance with Psalm 114: "What ailed thee, O thou sea, that thou fleddest? thou Jordan, that thou wast driven back?" Christ Himself blesses the water of the stream. To the left, two youngsters splash acrobatically in the water, while to the right two others dive in head first. These energetic children inevitably remind us of frolicsome Amors swimming about in some antique depiction of the birth of Venus. At the bottom of the icon, two symmetrical groups of Jews, holding naked children in their arms, gaze with wonder on this half-ceremonial, half-festive scene.

This icon, signed in Greek, teems with picturesque details, and was painted meticulously and clearly with great finesse in its drawing and color. A certain academicism led the artist to dampen the dramatic effect of the rocky landscape by superimposing the three angels upon it in poses of solemn reverence, while the ebullient antics in the water at Christ's feet contrast with the visionary scene above, which is rigorously constructed on a geometrical basis. Although the form of the painting is calculated down to the finest details, it is full of small but effective contrasts. Free of exaggerated tension, it is the product of a scholarly art which conceives everything in willfully aesthetic terms; it presents almost a kind of intellectual play that challenges the viewer to puzzle out the riddles for himself. Yet this icon shows no trace of the classicism which, in the first years of the fourteenth century, strove to revive antiquity in all its aspects. Only a few highly effective antique elements have been retained: the four allegorical personifications that are relegated to the marginal areas of the composition. In the mid-fourteenth century, Serbian churches and monasteries were particularly partial to such art as this — designed for connoisseurs, intimate and solemn at the same time, and closely related to manuscript illuminations. By the close of the century, with the first tragic blows against the Serbians by the Turks, this form of art fell back before the new tendencies. As early as the first half of the fourteenth century, the Serbian historian and archbishop, Danilo, could boast that in his time great princes presented the churches with "icons containing many holy relics." The appearance of such reliquary icons can best be judged from the sumptuous 197 diptych of the despot Toma Preljubovic, now in the treasury of the Cathedral of Cuenca in Spain.

VIRGIN. 1367-84. Left wing of the diptych of Toma Preljubovic, Cathedral, Cuenca, Spain

Since the icons by the same master were discovered in the Monastery of the Transfiguration at Meteora, we are better able to grasp this manner of painting: for in this example in Cuenca the painting itself is again almost concealed under a casing of silver studded with pearls.

There were tendencies in marked contrast in Byzantine art of the late fourteenth century and the first half of the fifteenth which could not fail to be reflected in divergent conceptions of icon painting. In Serbian and Macedonian regions two approaches dominated: one was linked to the tradition of the early fourteenth century, the other to the mural art of the mid-thirteenth century. The painting at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries — a style derived from Serbian prototypes of the first decades of the fourteenth century — is best seen in the fine frescoes in the Monastery of Kalenić.

THE FIVE MARTYRS (SAINTS AUXENTIOS, EUGENIOS, EUSTRATIOS, MARDARIOS, and ORESTES). End of 14th or beginning of 15th century. Museum, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos

The lavish use of color in those frescoes is carried over into an icon of the Five Martyrs from the Chilandar Monastery and to an icon of the saints Simeon and Sava, now in the National Museum, Belgrade. The manner of painting is close to that in an icon of Saint Demetrius in the Museum of Applied Arts, Belgrade, although the proportions and drawing in the latter case are still archaic. This icon originated in Salonica, and was painted for pilgrims who came to worship at the tomb of Saint Demetrius; despite its secure and noble draftsmanship, its gaudy coloring betrays the fact that it is a mass-produced work.

SAINT DEMETRIUS OF SALONICA. End of 14th or beginning of 15th century, Museum of Applied Art, Belgrade

The large icons in monumental style, intended for iconostases at the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century, are in complete opposition to the manner of painting just discussed. A series of icons from the well-preserved Deesis in the main church at Chilandar provides a perfect example of that late Byzantine art which somehow survived the catastrophic victory of the Turks and retained its high aesthetic standards well into the first decades of the sixteenth century. These are half-length figures of monumental muscular giants that remind us, in their way, of the creations of Michelangelo. While these powerful, strongly modeled, and discreetly colored melancholies were based on prototypes in the serene classical style — surviving in all of its beauty in Sopoćani — this world of impotent giants, living under the shadow of imminent destruction, is essentially the antithesis of its model.

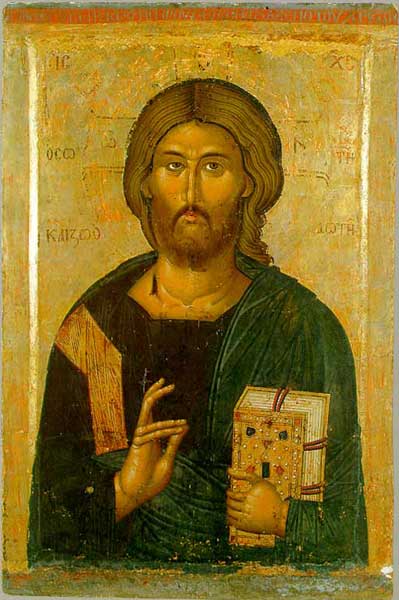

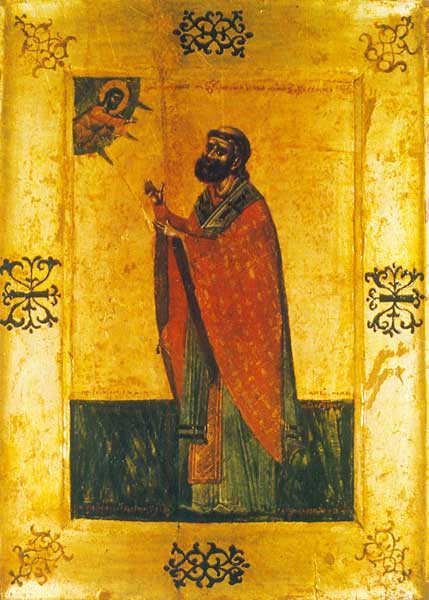

Jesus Christ Saviour and Life Giver, Mitropolitian John the icon-painter, 1384, Today - Museum of Macedonia, Skopje.

Bishop Jovan (John) was a prelate whose bishopric and lands lay near Prilep, and who withdrew to northern Serbia as the Turks approached. He was also an artist, known especially for the frescoes he painted in 1389 for the Monastery of Saint Andrew near Skopje. The bishop headed a group of painters that included two others known by name, his brother Makarios and the monk Gregory. An icon of Christ the Giver of Life by Bishop Jovan tallies perfectly with his monumental mural style, and also resembles similar large icons of Christ from that time, as well as the large icon of the Presentation of the Virgin in Chilandar. The bishop's brother Makarios worked during the first half of the fifteenth century in the unconquered part of Serbia, in the Monastery of Ljubostinja founded by the widowed Princess Milica. But he remained in contact with his brother's bishopric; and in 1422 he painted for the old monastery once connected with his family, as a commission from the monks who had stayed on there under Turkish rule, the exceptionally well-preserved icon of the Virgin of Pelagonia.

VIRGIN OF PELAGONIA. 1421-22. Painted by the priest-monk Makarios. Gallery of Art, Skopje

The icon itself is more interesting for its history than as a work of art. The product of an ordinary icon painter, it is something of a boundary marker between the periods of freedom and servitude, revealing that phenomenon of a return to the past that recurs with almost rhythmic regularity throughout the long history of Byzantine art. The noble, very finished work, imitating the refined style of contemporary Constantinopolitan art which characterizes the Kalenic frescoes and later the art of Novgorod, left few traces on panel painting. A double-faced icon from Ohrid, however, with heads of Saints Clement and Nahum, exemplifies the qualities of that peerless art which still continued to be practiced even after the Turkish invasion.

Manuscript sources and the first Serbian printed books give us only the scantiest information about the icons of the second half of the fifteenth century. Their general appearance is known from Serbian incunabula, in which ceremonial icons and icons of individual saints are illustrated in black-and-white engravings. Woodcuts patterned after icons, in the ecclesiastical books printed in Venice by Bozidar Vukovic, his son Vicenzo Bozidarevic, and other early Serbian printers, played an important role in the history of Serbian icon painting because they later served as models for other icons.

For two centuries Christian art had maintained its integrity within the Balkan interior despite Turkish rule, and it was even developed further in accordance with the principles and traditions of the older artistic culture. It was during those turbulent and uncertain times that the lofty iconostasis came to take its place in churches; the oldest extant wood-and-gilt iconostases date from the beginning of the fifteenth century. Generally considered to have originated on Mount Athos, they actually appeared in the Balkan interior at exactly the same time. Once their structure was fixed, these later Balkan iconostases clung for a long time to their two-story construction. In the lower tier were the four great icons; on the Imperial doors of the altar was the Annunciation, and above it, like a panel over the doors, the "unsleeping eye"; the upper tier contained several considerably smaller icons, with the Deesis in the center and six apostles on either side. Above the top row of icons, over the central door, loomed a large carved and gilded wooden cross with the crucified Christ, and the Virgin and Saint John. All the elements of such an iconostasis had long been familiar in Christian art of the East, but it was not until the beginning of the sixteenth century that they were combined in a rich, decorative unity. The new iconostasis, a simultaneous achievement of woodcarvers and icon painters, guaranteed that icons would have a leading role in the system of painted decoration of Balkan churches during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In addition to the principal iconostasis, Serbian monks under Western influence erected smaller iconostases with altars which were also carved and gilded. In 1627, there were eight such altars in Mileševa, and in 1662, thirteen in Studenica. Foreign travelers journeying the unsafe roads of the Balkans, who frequently put up at the monasteries, were astounded by the number of icons to be seen. In the mid-sixteenth century, Wolfgang Münzer reported having seen innumerable painted panels decorated in silver in Mileševa. At that time, icons were not confined to the iconostasis but were distributed throughout the church, some on special tables called "proskynetaria," others hanging in the great choir. More and more panels were painted, not only the large icons used in processions but also smaller ones for the series of liturgical feasts and calendars. Although icon painting in Serbian and Macedonian regions from the early sixteenth to the end of the seventeenth century certainly belongs to post-Byzantine art, it occupies a special position within the general framework. The consequences of the political collapse of Serbian secular power were acutely felt in the first decades of the sixteenth century. The more significant art works were created in the outlying regions to which the nobility had fled. In Krušedol, in the monastery of the last members of the Branković family in Srem, the upper tier of icons survives on the iconostasis, painted around 1515. During those same years the old, so-called Greek style of painting was revived in the western border areas of Herzegovina and Montenegro. Icons from around Dubrovnik are found both in Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches and are a mixture of Italian and Greek styles, though still closely bound to the Orthodox tradition.

In those years certain traits already appeared in the icon painting of the Balkan interior which were to remain constant for the next two centuries; notable was a stubborn insistence on orthodoxy. Even in their aesthetics, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century icons reveal a clear tendency toward conservatism. Consciously opposing Western naturalism, sculptural forms, and the lifelike rendering of space, Serbian icon painters of the later period borrowed certain ornamental elements from the East and certain types of stylization from Russian icons. In their basic conception they still clung to the old ideals, especially to the prototypes handed down from the fourteenth century. As late as the sixteenth century there must still have been many old icons in the great monasteries. Later artists in, for example, Dečani and Gračanica were surrounded by icons that were impressive as objects of worship and as works of art; these artists made a thorough study of the technique and artistic expression of their predecessors. Fascinated by the models at hand, they often painted icons that today may puzzle even specialists in the field; less experienced collectors sometimes date sixteenth-century icons too early by as much as two centuries. Nevertheless, the works that were deliberately fashioned in imitation of an older style still bear the mark of their own time: shadows are more pronounced and colors are subdued; the patina of age was merely imitated; and the tendencies toward literary conceptions and abstraction are marked.

Such works are clearly differentiated from the many variations of the Italo-Greek style as well as from Russian art. In adhering to the old iconography, the artists exercised a very exclusive choice of what to include and what to reject; this consistency became highly impressive in itself, and it led to these icons becoming sought after and revered, especially in Russia. We know from Russian documents between 1550 and 1699 that Serbian monks traveling to Russia took icons by native artists with them from their monastery treasuries as gifts to the court. Customs declarations issued at the border town of Putivlj show again and again that Serbian monks crossed over with icons, usually of Serbian saints revered as the founders or patrons of monasteries; these were stated to be gifts for the tsars, tsarinas, and crown princes, and on most of the forms appear the words "in gold." The interest in Serbian icons must have been very great in Russia during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There was even a Russian translation of a Herminia, a painter's manual, by an adventurer who purported, possibly fraudulently, to be a bishop, and pretended to be Serbian though he was more likely Greek: the handbook was completed in Russia on July 24, 1599, and the author was named as "Bishop Nektarios from the city of Veles," though he was probably an itinerant Greek painter who knew Serbian or Macedonian and lied about his identity (for one thing, Veles was never a bishopric). Be that as it may, this "Typikon" is a valuable source of information about fresco and icon technique in the late sixteenth-century Balkans. Research by Russian historians of icon painting was able to show that the book had considerable influence on the technique of later icons in their country. In Serbia itself, the later icon painters perpetuated the traditional methods of painting and composed handbooks and manuals. Among these is a very practical book of instructions, the

Book of the Art of Painting by the Priest Daniel from the Year 1674; the author had painted frescoes and icons in 1667 for the small Church of Saint Nicholas in Chilandar, which is still beautifully preserved.

SAINT GEORGE WITH SCENES FROM HIS LIFE. 17th century. Treasure of the Patriarchate, Pec

This insistence on traditionalism in technique, iconography, and aesthetic conception in no way reduced art in Serbian and Macedonian lands to the level of superficial repetition. The course of Byzantine art was marked from its very inception by successive returns to the past. The tradition-bound art of Constantinople drew its inspiration from the rich treasures of the church and from old, even antique, prototypes. This process of interpretation and re-interpretation was not the lifeblood of Byzantine art — as certain writers having a naturalistic bias have claimed — but the expression of the essence of the Byzantine conception: that is, that the holy and lofty origins of art could only be maintained through repeatedly restoring to life the models of the ancient past. Icon painting endured as long as that principle remained in force, regardless of the tragic circumstances attendant on the collapse of Christian political power in the Balkans. It is pedantic to divide Byzantine painting into two periods — the first authentically Byzantine, the second post-Byzantine — separated by the date of the final fall of Constantinople in 1453: Western influences did more harm to the art of Byzantium than the Turks did. With its own long history behind it and its principles clearly formulated, Byzantine art was free of the limitations that are inevitable in an art based on the observation and imitation of nature. Byzantine painting as a whole, and icon painting in particular, enjoyed an internal freedom within their own conventions, for they could profit from the subtle variations of aesthetic expression which continued to reappear, to merge, and to disappear regardless of the seeming external monotony of the formulas.

Unity of style in late Serbian icon painting was the product of drawing and composition. The palette had a range from black and white, through monochromy or intense polychromy, to the highly effective enamel-bright colors which were often used to underline or to interpret the inner, psychological values of the subject. The early Serbian predilection for narrative painting did not vanish in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Numerous icons were, so to speak, biographical: large panels with a saint in the center, surrounded by small scenes recounting episodes from his life. In these tiny, often miniature-like scenes filled with schematic and semiabstract forms, the events could not be illustrated realistically. Instead, they were transformed in many late Serbian icons into a stately ceremonial, or perhaps a dramatically expressive, pantomime or even into an almost childlike puppet play. But regardless of the form they assumed, the style of the icons remained "Byzantine" without alien elements from Renaissance or Baroque conceptions. True, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Balkan icons often sank to the naivete of mass-produced articles turned out for easy sale to village dwellers. Such productions, poor in quality and muddled in conception, are responsible for the oft-repeated judgment that the art of the Balkan peoples reached its lowest level under Turkish rule. But one gets an entirely different picture of the achievements of the art of the time when professional works are considered, for these were produced by outstanding masters whose names were known and who were proud to sign their works.

Icons of fine quality were made in Ohrid, Srem, Montenegro, and Herzegovina in the first half of the sixteenth century. At that time, Serbian and Macedonian icons did not differ from those by Greek artists. One of the loveliest icons in San Giorgio dei Greci in Venice, a well-preserved Last Supper with Saint Stephen and the Archangel Michael, which dates from the sixteenth century, is entirely in the Greco-Venetian style although it is signed by the famous Serbian printer Bozidar Vukovic.

ANNOUNCIATION. Church of Saint Tryphon, Monastery of Chilandar, Mount Athos. Center door of an iconostasis. Dimensions 4678X22In. Painted by George Mitrofanović, 1621.

After the Serbian patriarchate was reconstituted in 1557 a new art, in which icon painting took a prominent place, began to emerge in the broad territory under the jurisdiction of the reorganized church. The first distinguished icon painter was Longinus, an artist and writer belonging to the patriarchate of Peć, whose finest work was done in the Monastery of Dečani. Although he was active in the latter years of the sixteenth century, his paintings were often inspired by earlier Serbian literature. The greatest Serbian painter of the Turkish period, George Mitrofanović, earned his art in the Monastery of Chilandar on Mount Athos and achieved distinction as a painter of frescoes and icons. His masterpiece, the frescoes in the Chilandar refectory, is unques-ltionably the most significant achievement of Serbian painting done at Mount Athos in the early seventeenth century. Rich in content and inexhaustibly inventive, the frescoes show a spirited, precise draftsmanship that is in harmony with the lyrical, light, and refined coloring, and this synthesis produces an exceptionally fresh and original unity. Among the artist's followers two are outstanding: Cosmas and John. The rather enigmatic Cosmas, two of whose works survive, is famed for his great icon of Saints Simeon and Sava with scenes from the latter's life. In this imposing icon in the Monastery of Morača in Montenegro is concentrated a microcosm of mid-seventeenth-century Serbian icon painting: the full depths of the tragedy of a tradition-bound art stand revealed in this work which, at first glance, seems to be no more than a routine prodnct of a pedantic painter-monk. Yet Cosmas, like talented Serbian painters before his time, was tormented by an insoluble problem: in the same way that artists in thirteenth-century Mileševa continued to paint Byzantine frescoes although they were acquainted with Romanesque art, so this seventeenth-century artist subjected his work to the centuries-old rules of Byzantine painting although many fine details, which do not disturb the over-all unity, reveal his familiarity with the course of Western art. Cosmas' sensitive feeling for the values that dominated his traditional conceptions is reflected in his skillful manipulation of elements derived from the West to make them conform to the unshakable rules of his own tradition. The head of the deacon sunk in meditation, on the small icon that represents a scene from the life of Saint Sava, is modeled by contrasting light and shade and also has an intimate psychological intensity — both typical traits in Dutch portraits of the time. However, this head is in no way an alien intrusion in the Byzantine structure of the picture; thanks to the painterly conception, it is transformed into an element of beauty entirely characteristic of the art of icons.

THE SERBIAN PATRIARCH PAJSIJE. 1663. Painted by Jovan of Chilandar. National Museum,Ravenna

The painter John, Cosmas' contemporary from Chilandar, whose portrait icon of the Patriarch Pajsije in the National Museum at Ravenna is among the finest Serbian portraits of the seventeenth century, shows the same feeling for more intense and individual delineation of character.

In the last generation of Serbian icon painting, three names are particularly significant. Danilo, a priest from Chilandar, was a conventional, cold, pedantic technician whose works have survived in excellent state. Radul, painter for the patriarchs of Pec, was a prolific but uneven artist who had many mediocre followers. Finally, there was Avesalom Vujičić, a monk of the Monastery of Saint Luke in Morača, who was a restless adventurer and a fine artist. In his home monastery is the large icon of Saint Luke, the patron saint of painters: the small scenes from the life of the saint are especially valuable illustrations of the artistic environment of the time. Saint Luke is shown in his studio seated before an easel, rather like the usual depictions of the evangelists in their studies; but the saint is here surrounded by a clutter of objects all connected with the act of painting. Yet the great difference between artistic creation in the West and the East is brought out clearly here: in Western pictures of this subject — for example, the Madonna with Saint Luke by Rogier van der Weyden — the painter-saint works from a living model; in the icon, however, he relies on his own inner vision, since, even in this late Byzantine tradition, it would be unthinkable to show two Virgins on a single icon.

The fundamental character of Serbian icon painting, with its stern remoteness from nature, was perpetuated up to the end of the seventeenth century, thanks to the imaginative gifts of the Montenegrin painter-monks. But when the offensive of 1690 failed to regain the Balkans for Christendom, a new wave of Turkish terrorism engulfed the surviving monasteries, and the sparse . educated class which had fostered religious art took refuge north of the Sava River. It was only then that the social and material bases of the old art were finally lost. In the course of the eighteenth century, the Serbian refugees in Srem, Slavonia, and Hungary developed a new urban culture of their own and a new art which was not religious. In these new surroundings, icon painting was transformed into a native variant of orthodox Baroque art which, in the second half of the eighteenth century, blazed up in all its exotic beauty on Serbian iconostases. But once the wellsprings of religious inspiration had become dry and the entire creative process of the artist had altered, the art of the icon, too, passed out of existence. As the role of icons in the painted decoration of churches dwindled in the nineteenth century, they lost their character and their intrinsic value.

In the regions around Debar and Ohrid, the icon met a similar fate. In the early eighteenth century, the little-known Macedonian iconostases of wood, carved in low relief and then gilded, were more impressive for their sculpture than for their paintings. Among the most beautiful iconostases of this period is the finely carved and gilded one of Saint Nahum.

SAINT NAHUM OF OHRID. 17th century. Gallery of Art, Skopje

The early nineteenth century was marked by the emergence of the well-known, but often overestimated, wood-carved iconostases in Macedonian churches, executed in a lavish, peasant-inspired Baroque style overcrowded with carved foliage and figures. Lost in the chaos and exuberance of these decorative iconostases, the cold, hard painting of the icons degenerated into an unsuccessful attempt at a folkloristic style. The icon had become overripe as an artistic form and was fated to die out regardless of whether or not the Church was in a privileged or persecuted position.

There is some significance in the fact that during the seventeenth-century crisis in Russia, when the old way of painting was questioned and within the Church there were heated discussions about new art versus old, the Serbians were the most adamant defenders of traditional painting. In the manifesto of the new Russian school of icon painting, sent in 1664 by the artist Joseph Volodimirov to the famous icon painter Simon Uschakov, the Serbian archdeacon John Plečković was singled out for attack because of his stubborn loyalty to an archaic style. The attitude of the Serbians is easy to understand. As the westernmost Orthodox nation, they were the most exposed to the propaganda and pressures of the Union, and thus the most persistent champions of the orthodoxy of their art — even more than the Greeks. The old style of Serbian icons had been jealously guarded for confessional reasons and remained virtually untouched by Renaissance and Baroque influences right up to the end of the seventeenth century.

The degree to which icons in the Serbian and Macedonian regions continued to preserve their original artistic expression can be seen in a beautiful seventeenth-century icon of Saint Nahum from Ohrid. Painted after a model from the early fifteenth century that still survives, it remains faithful iconographically to its prototype but it does not try to match in its artistic treatment the refined subtleties of the earlier period. Instead, its more forceful drawing and subdued coloring spontaneously recall ways of painting which belong to the earliest history of the art of the icon.