MYSTERIOUS, far away India interested much our people in the Middle Ages. Vague news in that Age about the country, its people, animals and fruits contained however, scarcely a grain of truth. People only knew or sure that India was behind distant Persia and that lit was immense and rich. In the imagination of the medieval man it occupied the 'eastern part' of the world ; thanks to the few navigators who sailed to India it was certain that the sun shone there in the same way 'as with us'. In this strange mixture of fancy and imagination, which appeared for centuries in geographical works of the Middle Ages, India was the most remote from the real world. Because of this particular quality of being 'a dreamland', India was, on the whole the same in all the literatures of the European peoples in the Middle Ages.

Fantastic India was not a creation of the naive ignorance of the medieval man. Strange stories about India appeared already in the antiquity, which were to be repeated later on again and again. In the fourth century B.C., the Greek historian Ctesias wrote an uncritical, naive and curious work about India, almost a tale, in which strange Indian animals were described. Ctesias' texts have been better preserved in subsequent tradition than Aristotle's scientific researches on animals of the Far East. Fantastically rich men from India in the medieval stories were also familiar to ancient Romans. India was to them the native country of very rich men. In a Roman comedy, the prince of the tale appears as 'King of India'. Indian motifs in our medieval culture are frequent. They appear in different branches of literature and arl sometimes concerning India as a whole, but more often however, in fragments and in places one would least expect them. For our ancestors, the main sources of information about India were the 'Christian Topography' written by Cosmas Indicopleustes, the story of the Indian Empire, and the romance of Alexander the Great.

About 547 A.D. Cosmas, a merchant of Alexandria, wrote his Topography which, in its first version, consisted of only five books. India is described in the last two books which were added probably much later. Our translation from the original Greek appeared in the 15th century. The most beautiful Serbian manuscript of Cosmas' work was written in 1649 in the monastery c the Holy Trinity near Plevlje. The India of the last two books of Cosmas' Topography belongs almost to the realm of fancy. In this Topography, monsters have often been described, which arose in the lively imagination of the author as being born of crossing between real animals. The truth is distorted and stress is laid upon personal experience, as in sportsmen's tales. For instance, a monster is represented which resembles both the elephant and the boar; and to make it more probable, the caption explains: "I saw an elephant like boar and I ate it".

The most complete description of this imaginary India in our medieval literature is to be found in the romance of Alexander the Great, in the chapters where the campaign of India is described.

Hard battles against Porus, emperor of India, are particularly described in detail. Beside various exaggerations, a detail is mentioned there which truly corresponded to real Indian life, viz. elephants trained for combat with "towers" upon their back. Of the aptitude of Indians for war, we are informed by fragments on the Trojan War in the Chronicle of Constantine Manasses, which also was translated into Serbian in the Middle Ages. According to this text, Indians 'with a black face' took part in the battle of Troy led by Emperor Tavtant (Tantana, in the Greek text). The 'black men', either Ethiopians, Arabs or Indians, were considered as particularly dangerous in medieval novels. The single combat between Alexander the Great and the Indian emperor Porus is described in the romance of Alexander the Great as one of the most dangerous moments in the life of the young Macedonian monarch. It is interesting that the description of the single combat is almost literally repeated with other names in the well-known folk-song 'Prince Marko and Musa Kesedzija'. With great effort, by ruse, Alexander vanquishes Porus. Porus dies in this combat and Alexander enters the Indian capital, Indipolis. The description of Porus' palace exceeds all limits: its walls are of gold, the roof is golden, all the columns are of gold and decorated with pearls and precious stones. Golden statues and reliefs represent the twelve months ('in human figure'), the combats of all the great emperors etc. To give an idea of the manner in which Alexander's booty is described, it is enough to quote this detail: 10,000 lions and 20,000 leopards. It is not only conquerors who wandered in this land which glittered with gold and was suffocated with its riches. According to some apocryphal stories, even the Apostles went to India. To the naive authors of these stories, India was, as a heathen land, a centre of grave sins against one's fellowmen. The poets of our folk-songs in composing their own Persian letters in order to scourge the vices of the native milieu, made use of poetic license and placed the immorality of the subjugated Serbian population into India, the land of malediction. This unchristian India was a hard field for the Apostles. According to a Serbian manuscript from the 14th century, the apocryphal life of St. Thomas contains a detailed description of the way in which the incredulous Apostle converted, with many difficulties, the Indian people to Christianity. Completely fictitious stories about the experience of St. Thomas in the East were familiar already to our ancient writer Theodosius, who compared the activity of St. Thomas in India to the life of St. Sava on Mount Athos. Thomas' journey to India is described also in well-known apocryphal stories about the death of the Virgin. In the description of the events preceding the funeral of the Virgin, it is said that Thomas was late because he was far away in India. As all the Apostles—according to the same story—had at their disposal the quickest vehicle, the clouds, they flew back and arrived in time; only Thomas was so far away that his cloud was late for the funeral. Still —this story goes on—Thomas met the Virgin in the air at the moment of her Assumption. The episode of Thomas' journey from distant India has been often represented in our frescoes from the 14th century.

In both geographic and entertaining works of medieval literature, India has been described mostly by people who knew little about this land and invented pretty much. Much more interesting are the original elements of Indian culture, which reached the Mediterranean world in the Middle Ages. The rich Indian literature appeared early also in Europe in the Middle Ages. Parts of the Panchatantra and the complete life of Buddha, in the the form of the life of St. Barlaam and Josaphat, came into Serbian literature from India.

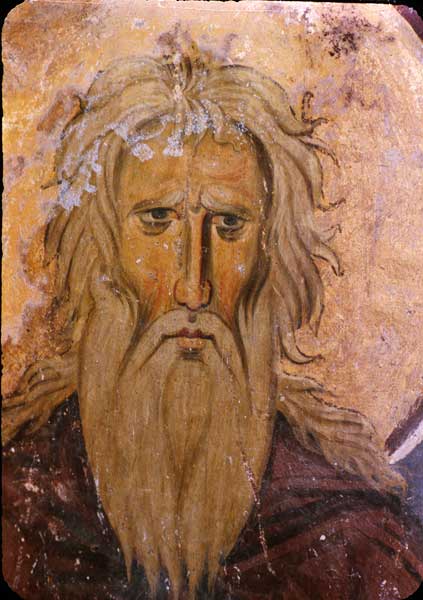

Studenica, Holy Virgin, Fresco, southwest pilaster, showing Barlaam

Through the Byzantine literature we received a collection of didactic stories entitled 'Stephanit and Ichnilat' ; they are parts of the Panchatantra, in which the educator of the sons of an Indian emperor tells didactic stories to his pupils. The extent to which these stories proved interesting to our people is evident from the fact that even in the 18th century, Matija Reljkovic imitated them. Of course, he did not do it in accordance with our medieval texts, but in accordance with a French translation from the Persian version of the same work. Different stories from ths Panchatantra have also been separately translated from Byzantine texts into Serbian. The story of the serpent in a collection of the Despot Stephan Lazarevic, is exactly the fifth story of the third book of the Panchatantra.

The most interesting borrowing from India in our medieval literature is at any rate the life of two saints, who never existed, the life of St. Berlaam and of his disciple Josaphat.

An article in the "Journal des Debats" of July 26, 1859 caused a great sensation among cultured people of that time. Edouard Laboulaye, a writer who was much interested in our literature and translated our folk-stories, maintained that the popular medieval legend relating to the Christian saints Barlaam and Josaphat was after all the life of Buddha. Subsequent researches showed that Laboulaye's assertion is true. An Indian book relating to Buddha had been adapted to the needs of the Christians, probably in the 6th century. Owing to an ordinary plagiarism, Buddha appeared in the Christian calendar with the orthodox as St. Joasaph and with the Catholic as St. Josaphat. Even in the Christian legend, the life of Buddha remained on the whole unaltered. This legend tells how the Indian emperor Avenir had a son named Josaphat, how the young prince, influenced by his master, the hermit Barlaam, began to hate this world, and how he himself became a hermit after his father's death.

Studenica, Holy Virgin, fresco, naos, southwest pilaster, showing Josaphat

In the Middle Ages, the didactic stories told by Barlaam to the prince were particularly popular; they have been often copied separately, as independent texts. The stories from this legend of Indian origin were introduced into nearly all the literatures of civilized peoples. The legend of Barlaam and Josaphat was translated also into ancient Slav. To the Serbs, the story of the Indian prince was familiar already at the beginning of the 13th century. The frescoes in the principal church of the monastery of Studenica show the figures of the two principal heroes of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat. A recently discovered inscription has shown that St. Sava was particularly in the painting of the church of the Virgin in the monastery of Studenica. The presence of 'Indian' saints is easily explained by this fact; St. Sava wanted evidently to show in the company of great saints represented in the central part of the church a monk of royal blood, because he himself was a prince. One hundred years later, in 1309, in the frescoes of the cathedral at Prizren, there appeared again a scene from the legend of the Indian prince.

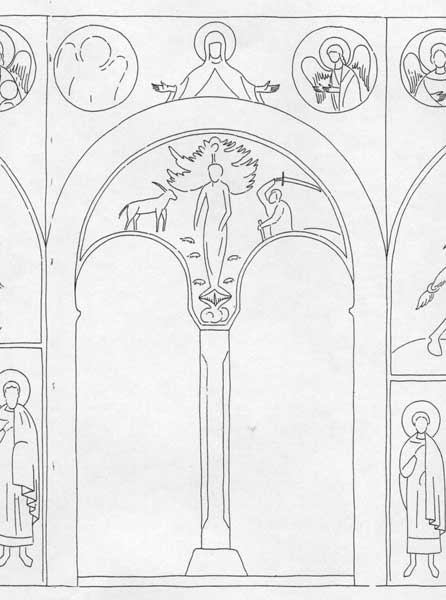

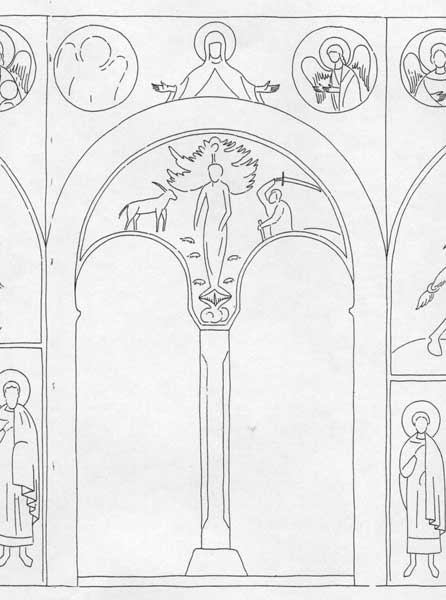

Prizren, Bogorodica Ljeviška, the catechumenion, west wall, linette: The Story of Human Vanity, from the novel about Barlaaam end Joasaph, 1307-1309

On the second floor of the bell-tower of the cathedral at Prizren is painted an unusual scene which looks quite puzzling at first sight. On the thin branch of a tree a man is hanging, upon whom rushes a phantastic animal, a unicorn. This man in danger is described in detail in a story relating to the legend of Prince Josaphat; the same man hanging on a tree, a symbol of the 'transitoriness of pleasures of this world', is represented in the great basilica of St. Demetrius at Saloniki. Stories from the legend of the Indian prince spread particularly by means of illustrated, commented psalters. The same scene which has been represented in the cathedral at Prizren is to be found in the famous Serbian psalter of Munich from the end of the 14th century. This scene appears later in Russian psalter from the end of the 14th century, as an illustration of psalm 143.

Serbian psalter of Munich from the end of the 14th century, scene from the novel of Barlaam and Josaphat

Buddha's life, in this Christianised version, became at the end of the 14th century the favourite model of hesychastai, monks who belonged to the strongest religious movement in the late Byzantine Empire. The famous hesychastes, polemic and writer, Gregorius Palamas, was a particular admirer of St. Josaphat. In the church of St. Demetrius at Saloniki, one fresco representing Gregorius Palamas in company of the holy prince Josaphat has been preserved. John Cantacuzenus, Emperor of Byzantium and known writer, also a protector of Palamas, took the name of Josaphat when he became monk in 1354. The last of the Nemanjides, Prince John, Emperor Dusan's nephew, was also inspired by the example of St. Josaphat. He became monk in 1381 under the name of Josaphat. A miniature in the manuscript of a work of the emperor John Cantacuzenus, now at the National Library in Paris, shows best to what extent Buddha, as the Christian hermit Josaphat, was revered in the second half of the 14th century in the Christian East.

This Paris manuscript contains a double portrait of the author, within the same frame John is represented, at left, as the emperor of Byzantium in Imperial robe, and, at right, as the monk Josaphat in the modest black gown of a hermit. It is rather difficult to understand now that a borrowing from Buddhist literature was able to inspire men who created the history of their own times, as monarchs, polemics and writers.

Indian motifs in our medieval culture are quite varied. The naively depicted figure of the Emperor Porus, inspired by the romance of Alexander the Great, in the monastery of Temska, inspired folk-stories. The 'tree of life' in the cathedral at Prizren, borrowed from the stories of the life of St. Josaphat, influenced at all events the spiritual life of citizens of the ancient capital of the Nemanjides. The most active minds of the late Byzantine literature were interested in the complete text of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat. If it is ever possible to speak of 'fruitful illusions', India in our medieval literature was really a source of curious inspirations which influenced the decisions of important historical personalities and which fecundated the imagination of writers, painters, and composers of folk-songs and folk-tales.

The tale about India grew in the imagination of all European peoples, from ancient Greeks onwards to the end of the Middle Ages. This illusion which crystallised for centuries, was embellished and exaggerated in the domain of art, it was a constant hyperbola. In the early days of modern European culture, in the Middle Ages, it was the land of every possible poetic license, exactly that land of which the 'guslar' sings to our peasants:

I shall bring you to India

Where the mint grows up to the knees of horses

And the clover-grass up to the shoulders,

Where the sun never sets...

Without differing much from the others in exaggerating India's strange particularities, our people, however, described it in their own way, as a paradise for shepherds. So it happened that the India of our ancient literature and art resulted, in its original and natural end, in the India of our folk-songs.

The Indo Asian Culture, April 1957