During the reign of Prince Lazar and his son Stefan, an architectural style developed in the Morava basin which was wholly dedicated to ornamental and the picturesque effects. This style was of short duration (it lasted about forty years), and it reached its culmination in Kalenić. Never in old Serbian art did painted architecture approach so near to the actual one as in the years between 1370 and 1410. The Serbian churches dating from this period seem enwrapped in a luxurious network of minute stone ornaments carved in low relief and painted in lively colours, which follow faithfully in drawing and colour the motifs of miniature painting. The technically difficult effort to make the unbridged — and yet minutely exact — fantasy of painted architecture live in the monumental form of an actual church building could not be sustained for long. The architecture of the Serbian Morava school had the transience of an experiment. The efforts of the architects of the most decorative buildings of the Morava Serbia to achieve an unattainable and untenable wealth of form and colour soon provoked a reaction which became chearly manifest in Despot Stefan Lazarević's last and largest monument, the Temple of the Trinity, his tomb-chapel in the Resava monastery (Manasija). The last and largest of the churches of the Morava school was decorated with quite modest carved stone ornaments.

The rapid rise and fall of the decorative movement in the architecture of the Morava school seems to have been connected with the activity of a few masters who built churches for the members of the families of Prince Lazar, Stefan Lazarević, and their nobles. Although short-lived, this art reigned supreme during the years in which it flourished.

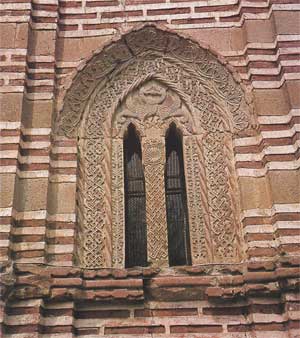

The monastery of Kalenić, 1407-1413.

The most beautiful and best preserved monument of this original decorative school of old Serbian architecture is the small church of the Kalenić monastery. Its whole exterior is adorned with minutely carved stone decorations, the drawing and colours of which are adopted directly from miniatures; while the technique itself of low relief is borrowed from carved wooden decorations in the same style. Applied in an original way and often with the naivete of a provincial art — especially in the treatment of figural reliefs — this decoration even today maintains the full freshness of its densely concentrated and patiently expressed fantasy. Today it is difficult to visualise even with approximate accuracy how these multicoloured red-violet-green-yellow and blue-white ornaments on the facades of the church merged with the polychromatic ornaments of the surrounding wooden monastic cells.

In spite of its links with the ornamental designs of manuscripts, the exterior decoration of the Kalenić church is logically subordinated to the basic architectural conception of the whole. The clarity of the architectural elements is in no way impaired by the exuberance of the ornaments; they flourish on the frames of the portals and windows, on the richly moulded arcades and luxuriously intricately perforated stone rosettes of the circular windows.

Biphora from Kalenić

The restless polychromy of the upper wall surfaces lends a certain lightness to the masses enclosed within the austere, restrained vertical lines of the western and main cupolas.

In the exterior architecture of the Kalenić church the rational element is skillfully concealed by the decoration; in the decoration of the interior everything is subordinated to a strict logic, including the arrangement of space and their painted decoration.

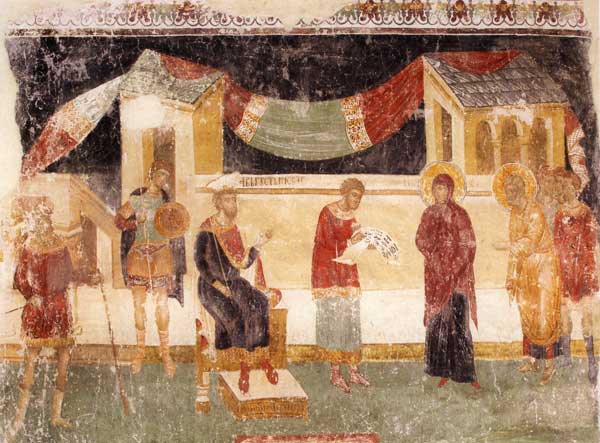

Despot Stefan Lazarević

Between 1407 and 1413 anonymous masters constructed and painted the church of the Kalenić monastery for Bogdan, a noble who held the rank of protodocharus at the court of Despot Stefan. On the north wall of the narthex is portrayed the founder's family: Bogdan with his wife Milica and brother Petar; and in front of them stands Despot Stefan. The same hieratic discipline is evident both in the founder's law and in the painting; just as the noble was obliged to submit his founder's charter for approval to the despot, so he is placed in the founder's picture behind the despot, who retains the advantageous position of mediator between the donor and the sacred persons to whom the church is dedicated.

The selection and arrangement of paintings in Kalenić is carried out in a careful and systematic way. About the middle of the 14th century the narrative tendency was dominant in Serbian wall painting; numerous cycles jostled each other on the church walls in a rather arbitrary way. But towards the end of the century the artists suddenly become more restrained; the subjects were carefully selected, and great sensibility was displayed in bringing their arrangement into harmony with the interior architecture. In Kalenić the relation of the fresco to the space and the wall surface is always carefully studied: the proportions of the figures and compositions (scenes) are perfectly adjusted to the dimensions of the interior architecture.

The calotte of the dome contained a large medallion with the bust of the Pantocrator; round him circulates the solemn procession of the celestial liturgy, and below — in the circle of the tambour and between the windows — stand the eight great prophets; beneath them is a circular painting of twelve prophets. Seated evangelists are represented in the pendentives.

Between the evangelists are the Veronica on the east, the Keramion on the west, and the Hand of God on the north and south. The proportions of the figures in this space are skillfully differentiated. The figures of the evangelists are the smallest, the prophets below the windows are slightly larger, the prophets between the windows are considerably larger — and Christ in the calotte is certainly the largest. The figures grow in size as they rise upwards.

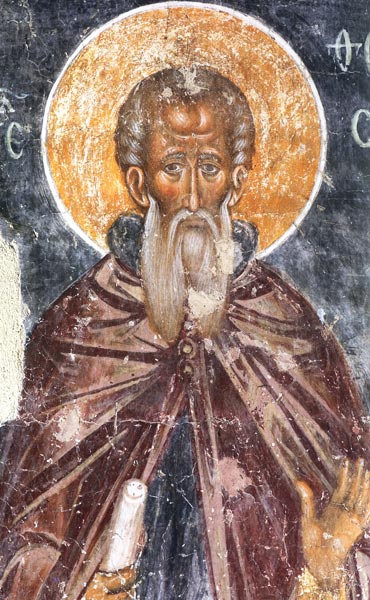

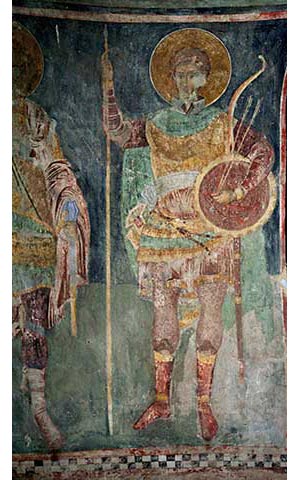

Saint Theodosius

The double gradation is carried out simultaneously: in conformity with the scale of ideal values, the more important persons are larger than the less important; the other gradation was introduced for a more practical reasons: all forms further from the eye are painted in a larger size so that they can be seen better; the ornaments and inscriptions in the upper zones are also considerably larger. In the temples, in the vaults and the uppermost zone, the great feast-days were represented, but only a few of these have been preserved: the Annunciation, a small part of the Nativity of Christ, Presentation in the Temple, part of the Ascension, the Descent into Hell, and part of the Ascension of the Virgin.

The idea of the altar as the symbol of Christ's Sepulchre, a favourite one in late Byzantine theology, is specially emphasized in Kalenić. In addition ito frescoes representing the Adoration of the Lamb of God and the Holy Communion of the Apostles, which were obligatory parts of the decoration of the altar space, there are detailed scenes from the story of the Resurrection: John and Peter at the empty Sepulchre (John, XX, 1—9), the journey to Emmaus, the supper at Emmaus, and the return of Luke and Cleopas to the Apostles (Luke, XXIV, 13—36). The niche of the deaconicon contains a painting of the Virgin — Oranta, and in the proscomidia is the well-known fresco representing Christ in the Sepulchre which may be said to be the most beautiful Imago Pietatis (Pieta) in Byzantine painting.

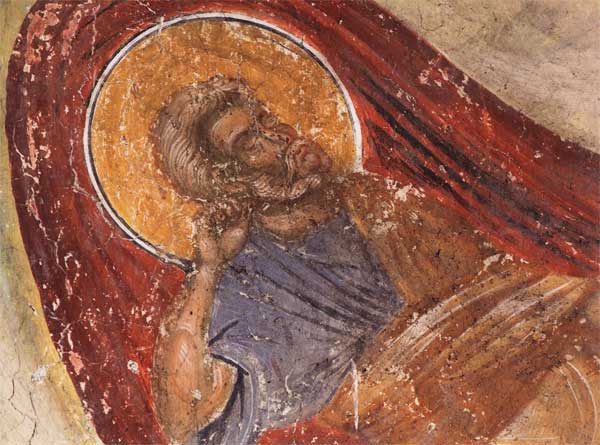

In the middle zone, above the standing saints, is a iseries of scenes representing Christ's miracles. The cycle begins in the eastern part of the south concha with the miracle in Cana of Galilee (John, II, 1—11); next to it is a painting representing the heading of the daughter of Jairus (Matthew, IX, 18—25). The cycle continues on the western wall with the healing of the daughter of the woman of Canaan (Matthew, XV, 21—28) and the multiplication of the loaves (Matthew, XIV, 15—22). In the northern concha the cycle of miracles ends with the following scenes (from west to east): the healing of the man who had dropsy (Luke, XIV, 2—5), the healing of the leper (Mark, I, 40—45), and the healing of the two blind men (Matthew, IX, 27—30).

The healing of the leper, detail

The selection of standing figures of saints in the first zone is characteristic. Places previously alloted to the Apostles are given to the warrior saints. In the south apse of the choir are St Demetrius, St Nikiphorus and tooth St Theodores — Tyron and Stratelates. On the front of both pairs of pilasters stand archangels, Gabriel on the north and Michael on the south. In the western part of the church in the lowest zone, are painted St Simeon of Serbia (Nemanja), St Cyric and St Julitta, St John the Blessed, St Nicholas, St Constantine and St Helena, St Kosmas and St Damianos, St Sava of Serbia and St Sabbas Stratelates.

The absence of Apostles in the first zone of frescoes seems to indicate that there was a two-storeyed wooden iconostasis with icons of the Apostles in the upper row, in the frieze of the Deisis.

The frescoes in the narthex are perfectly adapted to the rather intricate surfaces of its interior architecture. Above the standing figures acre arranged, in four zones, scenes from the childhood and youth of the Virgin, and illustrations from, the Nativity cycle.

In the highest zone, below the blind cupola in which no paintings have been preserved, four scenes can be discerned from the apocrypha, showing Joachim and Anna and illustrating events before the birth of the Virgin: the presentation of gifts, the return of the rejected ones, Joachim among the shepherds, and the angel announcing that a child will be born to Anna. In the second zone on the east wall the birth of the Virgin is painted, and next to it, on the south wall the caressing of the little Virgin, on the west wall is a picture of the Virgin and the three priests, and on the north wall is a painting of the first seven steps of the Virgin. In the third zone, beginning in the east, are the following scenes: the Confirmation, the prayer of Zacharius in front of the rods, Zacharius bestowing the Virgin on Joseph, the Annunciation at the Well, Joseph reproaching his betrothed, and the meetiing of Mary and Elizabeth", here the cycle of the Virgin ends, and the Nativity cycle begins. In the third zone on the north wall, out of sequence, the Nativity is painted round the oculus. In the fourth and narrowest zone, on the east wall, events before the Nativity are continued: the angel explaining to the sleeping Joseph the conception of the Virgin (Matthew, I, 19—24) and, after this scene, the Journey to Bethlehem. On the south wall — in the same zone — a rare scene is painted: the Taxing of Joseph and Mary (Luke, II, 1—5).

Joseph's dream: Joseph is warned to fly into Egypt

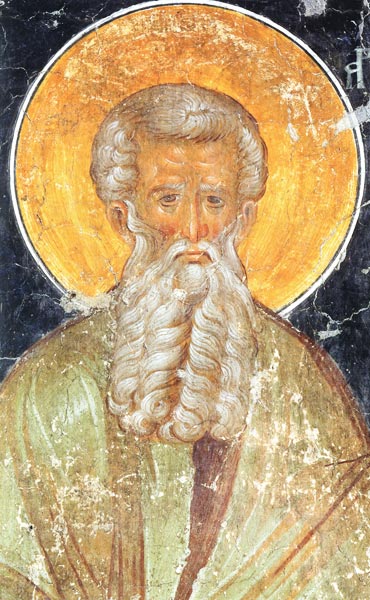

Omitting the scene of the Nativity, which he placed in the third zone of the north wail, the painter goes on to illustrate events after the birth of Christ: the adoration of the Magi, their journey home, Joseph's dream in which he is ordered to flee, and, on the north wall, the Flight into Egypt. The standing figures in the lower zone are distinctly grouped. On the east wall is the Deisis; in the linette of the portal is a head of Christ; on the north section of the wall is the Virgin with the Apostle Peter, on the south part of the wall are St John the Baptist and the Apostle Paul. The remaining surfaces of the lowest zone in the narthex contain pictures of holy hermits: Antonius the Great, Arsenius, Ephtimius, Atanasius of Athos, Theodosius Kinoviarchus and Ephremius of Syr.

Saint Arsenius

In Serbian churches dating from the late 14th and early 15th centuries, warrior-saints usually stand in the naos and the hermits in the narthex. In the third quarter of the 11th century the selection and appearance of figures in the lowest zone varied greatly. In the regions of Macedonia, from Castoria to Skopje, in churches dating from about 1370, the large standing figures in the lower zone evoke the atmosphere of the celestial court. Dressed in the fashionable clothes of 14th century courtiers, holy warriors in long robes, and high headpieces are represented on a low base — almost identically dressed as the nobles of those times. In paintings from the second half of the 14th century the celestial court, la Cour celeste, very similar to the courts of the Emperors Dušan and Uroš, is painted as an expression of confidence in the stability of temporal power.

Saint George

Choirs of hermits land warrior saints succeeded each other, according to the wishes' of the founders. In monastic churches the hermits are in the naos, and the warriors in the narthex (far example, in 'the Zaum Church, Lake Ohrid); in noblemen's churches warrior saints in aristocratic dresis take the more distinguished place in the naos (for example, in Marko's Monastery near Skopje).

The warrior saints in long robes and fantastic headdresses, the last echoes of the pristine temporal glory of the nobility, are painted in the southern, Macedonian regions, up to the early 16th century. In the northern parts such warriors are dressed in the ancient armour of classical soldiers; only some detail — an unusual cap or a curved Turkish sabre — indicates the period in which they were painted. In the majority of churches of the Morava school the warrior saints are represented with brisk movements: impatient soldiers before the battle examining their arms, testing the sharpness of their swords and the precision of their arrows.

In Kalenić the warrior saints are not so restless; the majority of them are calm, relaxed, gazing into the distance.

Only two are painted with slightly livelier movements: St Theodore Stratelates, who is drawing his sword from its scabbard, and St Procopius, who has drawn his sword and is holding it straight in a solemn way, as at some ceremony. The same calm, elegant, ceremonial attitude, evident in the first rank of the warrior saints, can be seen on the other frescoes.

The new decorative quality and elegance in the proportions of the human face, in the attitudes and movements of the figures, is evident even in the earliest frescoes of the Morava school in Ravanica.

In the clearly formed system of decoration which emerges in Ravanica as a well-defined whole there is an especially remarkable theme which occurs in the majority of churches of the Morava school: a frieze of medallions with small circles in between; in Serbian medieval painting it is only in the Morava style that this motif occurs — a wide indented band interwined in figure-eight pattern, and forming a series of interlinked small and large circles. This decorative frame of busts, often used in Byzantine art, is particularly frequent in reliefs of ivory. The Serbian masters of the Morava school faithfully adhered to these patterns from sculpture. If we compare, merely by way of illustration, the medallions of the famous Vatican triptych with those of the Morava artists, it becomes evident that this direct reversion to 10th century models could only have taken place in Constantinople. This remarkable element, however, external, is not a solitary phenomenon. The types of heads, too, and the refined proportions and postures of figures in the Byzantine reliefs of the 10th century frequently remind us of the elegant saints of the Morava churches.

In style the paintings of Kalenić differ considerably, from the frescoes of the Morava school. The frescoes of Kalenic have clear links with the 14th century art of Constantinople, particularly with the mosaics of the Kahrie Mosque.

Iconographic similarities between the frescoes of Kalenić and the mosaics of Kahrie Mosque were noted long ago. It is enough to mention the rare motifs of the taxing of Bethlehem: both compositions in Constantinople and in Serbia, were made on the basis of the same drawing. Nevertheless, in spite of surprising similarities, essential stylistic differences are apparent even in the closest parallels.

All arts which do not aspire to express something new have a strange power to effect a basic transformation of their models by means of small changes. From the last years of the 14th century the Serbian art strove after immutability. The luxurious art of the Morava Serbia was spun out of a dream of the splendour of the distant past. The more recent past was discredited. The picture of heaven and the heavenly host could not resemble the court and army of a ruined empire. In the years of the Turkish invasion Dušan was looked on as a sinful emperor who had incurred the wrath of heaven by his pride. The temporal Christian armies were helpless. After the Kosovo disaster in 1389, Jefimija, a nun, lamenting the death of Prince Lazar, calls upon the warrior saints to join in the battle. Calling in dispair on each of them by name, she appeals to the dead prince: "Call a meeting of your friends, the holy martyrs, and with them pray to God who made you glorious; send word to Gregorius, move Demetrius, persuade Theodore, take Mercuriuis and Procopius with you..." This mobilization, of the church militant did not have much effect on the warrior saints in Kalenić. In all other monasteries of the Morava basin they draw swards and dart restless looks around, as if searching for the enemy, "armed with weapons in their right and left hands", as Constantine the Philosopher puts it so vividly. In Kalenić the soldiers of the heavenly host stand calmly, awaiting the decisive battle, without apprehension: dignified, confident and still. This clear insistence on the inward values of main is one of the most prominent feature of the Kalenić paintings: a discreet restraint in expression.

The Numbering at Bathlehem

It is sufficient to compare two representations of the same subject, from Kalenić and Kahrie Mosque, which are very similar at first glance — the illustration of the taxing (Luke, II, 1—5): the arrangement of figures is almost identical; in Kahrie Mosque the legate Quirinus, marked in Kalanić as Emperor Augustus, is seated on the left, while behind him stands a member of the guard holding a spear, a shield and a sword; in front of the legate, in the centre of the composition, stand a scribe and a soldier; the "Virgin is in front of them, with Joseph and three peasants behind her.

In Kalenić only one change is made in the arrangement of the figures: the soldier in front of the scribe is placed at the far left of the painting. This single stroke changes the whole situation. In the mosaic of Constantinople the power of temporal power dominates, the Virgin answers with bowed head to the soldier who examines her, while the scribe records her words silently. In Kalenić the Virgin stands erect, while the scribe before her is slightly bowed. The soldier who examines her is behind the member of the guard. The Virgin speaks — not with Quirinus, the imperial legate, but with Augustus himself. The general conception of the same incident, as well as its artistic execution, are completely different. In the Kahrie Masque the dramatic moment of the Virgin's embarrassement is represented by animated movements in a shallow scene. The obtrusiveness of the gestures and forms is enhanced by sharp contrasts of light and shade.

In Kalenić, in a considerably deeper space, the same scene is represented, but the action in it ils barely suggested. The expressions on the faces communicate more than the gestures. The gentle, pale colours of the modest architecture in the background, with heavy drapery above the roofs, provide a warm and intimate framework for the whole scene. The dramatic accent is shifted from the action to the inward life of those represented. The former loud tone of narration is subdued and refined. The artistic elaboration is carried out unobtrusively. An almost concealed harmony, unnoticed at first sight, dominates the drawing and the colours.

The perfection of the formal and aesthetic treatment of old motives in the works of the Kalenić masters can be best seen in the superb composition of the fresco representing the Wedding in Cana of Galilee.

Kalenić, The wedding at Cana, detail

In earlier representations of this scene, such as in the Church of St Nikita and in Gračanica, both dating from the early 14th century, a multitude of guests — which was the reason of the scarcity of wine — are represented; in Kalenić, however, we have a selected group: Christ and the Virgin, the newly married couple, the governor of the feast, another elderly man, and three young servants. The nine persons are carefully arranged round the table and the large vessels. Three groups are sitting at the table. On the left, Christ and the Virgin are placed apart from the others. The mother says to her son: "They have no wine"; and Christ answers her sharply — the only time in the Gospel: "Woman, what have I to do with thee? My hour is not yet came".

The two elderly men at the other side of the table, in cornu sinistra, are tasting the new miraculous wine, but both the governor of the feast, who is raising a glass, and his companion are listening attentively to Christ. Only the bride and the bridegroom at the lower end of the table, with tenderly bowed heads, are performing a ceremony of their own, not mentioned in the Scripture: the bridegroom is about to prick the finger of his bride with the pointed tip of his knife. The play of gesture is admirably conceived to the minutest detail: the bride's hand is reposing gracefully on the richly embroidered tablecloth; it is being approached by the bridegroom's hand holding the knife like a surgeon's instrument and tense with concentration. In the earlier art, hands, being invariably stiff, were not capable of such eloquent gestures. The rite of the young couple is clearly illustrated. According to a very ancient non-Christian custom, the bridegroom and the bride drink blood mixed with wine out of the same glass, which is held between them by the bridegroom. The typically Serbian mixture of pagan and Christian rites is here brought into harmony by the power of the artistic execution. Two stories of blood are added to the New Testament description of the Miracle in Cana.

Kalenić, The wedding at Cana

Tragic symbolism was attached early to the apparently trivial wedding-day anecdote about the shortage of wine: the wine in Cana was interpreted as Christ's blood. A church song which is sung on Good Friday describes the meeting of the Virgin and Christ on the way to Golgotha;. At the time when the "hour" referred to at the table in Cana is drawing near, the Virgin asks Christ if he is going to "another wedding in Cana". And in this picture — in the centre — we also have a representation of the primitive blood myth, which survived until recently in the Montenegrian rites of ceremonious confirmation of friendship. As recently as the thirties of the present century the ceremony of the confirmation of friendship was performed in this way at Kuči.

Christian symbolism and papular superstition are merged in the spectacle of a medieval aristocratic feast. The wedding scene in Kalenić reminds us of a passage in Constantine's Life of Stefan Lazarević, describing the refined manners at the despot's court: "And all of them were like angels... and (behaved) with great decorum and modesty... Noise or tapping of feet, or laughter, or awkward clothes might not be even mentioned, and all of them were dressed in light-coloured robes which he himself used to give them ..."

The Kalenić fresco of the Miracle in Cana expresses the same elegance of manners and grace of gesture and dress. The strict symmetry of the three groups of persons seated at the table is also exporessed in numbers: two, three, two. And yet the composition as a whole is not enclosed within this austere numerical symmetry; it is relieved by skillful emphasis on the right section of the picture: the water-pots in which the water is turned into wine. The unequal masses which disturb the balance, the table and the water-pots, are cleverly interlinked by means of the dark surfaces of the robes: Christ's, the Virgin's and the bridegroom's on the left, and those of the seated guest and the two servants on the right. The well-planned arrangement of persons dressed in dark clothes results in a new symmetry embracing the whole scene.

A fresh picturesque quality begins to emerge in the style of the Kalenić masters. Although the human figure, as a plastic form, is clearly defined, it loses its earlier statuesque stiffness and weight. In the composition of the Kalenić frescoes man is a light or dark blot with vivid contours. The earlier obtrusive antrapocentrism is subdued to such an extent that some of the frescoes resemble those of western art; the high complex architecture in The Adoration of the Magi, and the extensive landscape with architecture in the Flight to Egypt remind one of Italian art. These compositions are not typical of the practice of the Kalenić masters, but they nevertheless indicate their interest in subjects which the other Byzantine artiste of the time treated in a much stiffer and more stereotyped way.

The Flight into Egypt, detail

The new sense of totality of expression and impression is superbly displayed in the frescoes of Kalenić; though the details are carefully executed, everything is subordinated to the dominant conception. Varied physiognomies and characters, which were very popular in Serbian painting of the 14th century disappear in Kalenić: the type of young men, warriors, old men, women become more uniform. The artist is not interested in the striking external features of the face; he rather strives to give an intense expression of inward feeling. The gravity of countenance as a reflection of virtue persisted in Byzantine art to the very end, but the variants of this gravity, especially on the faces of individual figures, were innumerable. The grave figures of Kalenić do not greatly vary: the younger ones are pensive and resolute, the older ones anxious, apprehensive, almost plaintive.

St Theodosius in the narthex of Kalenić looks as if he is about to burst into tears. The Morava artists, oppressed with the tragic atmosphere of the times, did not care to represent faithfully individual transitory features; they were not interested so much in the external features of thier generation as in its dark foreboding of its approaching end. Seen from this point of view, all the figures of the Serbian Morava painting represent a homogeneous gallery of joyless people.

The miniature of St. Luke, with a bull by the master-painter Radoslav come from a New Testament dating from 1429, now in the Saltykov-Shchedrin Public Library, Leningrad.

Almost the same faces are painted by the anonymous Kalenić artists and by Radoslav, the author of the miniature of the Evangelists in the Serbian Leningrad Gospel of 1429, as well as by the anonymous artist who painted the grand frescoes in the dome of Monastery of Manasija. The same spirit permeates the illuminator Radoslav and the unknown author of the monumental prophets in Manasija.

However, this strong similarity is confined to the facial features; as regards their psychological and artistic treatment, all these externally similar heads are essentially different: the sorrow of the gigantic and mighty prophets in the cupola of Manasija seem to anticipate the dark, titanic moods of the Sixtine Chapel; the lyrically helpless St Theodosius from Kalenić, too elegant and refined, evokes affection rather than respect, and the old John of the Leningrad manuscript — who has the same countenance — almost borders on the ludicrous with his grimace of a frightened old man.

These heads are very different in artistic conception, too. The later frescoes of Manasija are to a certain extent archaic, dominated by the traditions of wall painting; their heavy, hard forms are sharply lit. The luxurious colours of Radoslav's miniatures, according to a description of N. P. Kondakov, glitter with soft tones, violet, green and blue. Dark golden lines, drawn in melted gold, cover the choth, wood and metal like scintillating gossamer—all this reminds one strongly of the technique of icon painting.

The light, transparent colouring of the Kalenić frescoes is an isolated phenomenon in the Serbian painting of the early 15th century. light brown, light red, strong yellow, light green — all these favourite colours of the Kalenić artists were rare in other old Serbian paintings. Neither before Kalenić nor after it do we find similar frescoes in the despotic state of Serbia.

Three conspicuously new features appear in the structure of the Kalenić style: light colours, subdued plasticity of the human face, and Strongly emphasized lines. As a result of these novelties, a reverse relationship is established between the human figure and the landscape or architectural setting. In the earlier painting the human figure was dominant, and the architecture or landscape was represented in the background in diminished, toy-like forms; in the best frescoes in Kalenić, however, the human figure becomes suddenly ephemeral, almost negligible. The Magi pass hastily across the scene, almost like shadows, before the towering, massive architecture which forms the background. A new process begins in which inanimate objects and natural scenery becomes larger and more solid, while the human figure, represented by a nervous arabesque, becomes smaller.

The specific features which distinguish Kalenić painting from all other Serbian painting of the Morava school can be explained dearly enough: the anonymous Kalenić masters strove more after the transcendental than the other Serbian artists of the early 15th century. The Kalenic frescoes — viewed within the framework of the Morava school — have something almost ethereal about them. Nevertheless, if we compare them with the Russian paintings of the early 15th century, we see clearly that they are products of an art which has not abandoned the realistic basis of its style.

The Numbering at Bathlehem, detail

The plastic quality of the human figure in Kalenić is not obtrusive, but it does exist and is always suggested clearly. A certain lyrical quality and detachment from the realism of the average, lend the scenes of the Kalenić painters the exotic atmosphere of an Oriental fairy tale. The newly awakened interest in natural scenery and a more natural relationship of man towards his environment is mixed with a tendency to introduce well-observed and carefully reproduced details of Oriental luxury. The isolated art of Kalenić is obviously the art of an isolated society prepared to meet its doom. It was also a nobly condensed art. The whole Morava school was permeated with trends from Constantinople, from Thessaloniki, from Mount Athos, from Bulgaria, and via Dalmatia, from Italy. It is not without reason that Kondakov, in this discussion the Serbian paintings of the early l5th century, refers to a certain dignified look on the faces in Serbian miniatures. As a result of Turkish pressure, many writers and artists from threatened or already conquered lands fled to Serbia, which they would not have dreamt of coming to in normal circumstances. Thus Serbia became a refuge of foreign intellectuals and artists whose activity had a sudden revivifying effect on the artistic life, giving it to a certain extent an international character.

In the Serbian despotic state, especially in the ranks of the highest nobility, artistic traditions were strong; the new trends could therefore establish themselves, and assume new features supplied by Serbian art. This Serbianised art existed in Serbia only as a transitory phenomenon; and before the final disaster, being the art of emigrants, it moved north to Vlaska and Moldavia, and thence to the remote and vast regions of Russian ant. There was a certain logic in this migration. The monumental branch of the Morava art died on its own ground; the court painters of the Lazarević and Branković dynasties did not emigrate; there are no traces whatever of any later paintings corresponding in style to the frescoes from Manasija. But the minor art of the provincial artists — of those who painted Ramaća, for example — survived in peasant communities under the Turks.

The art which migrated was the art of the high nobility, that is, of the class which supplied the greatest number of emigrants. This art was even then ready for migration. It had deliberately broken its links with the soil from which it derived its strength. The helpless beauty of the Kalenic frescoes reflects, as in a mirror, the whole tragic sense of the later Serbian knighthood: its elegance, discreet decorativeness, subtle sense for restrained attitude and gesture express the outlook of an exclusive and cultured society, rich and helpless, striving to emigrate, in the full splendour of its mellow culture and with all the comforts of its easy life, from an insecure earth to a secure heaven.

Rublov's icon "Holy Trinity" and the Kalenić group of the bridegroom, the bride and servant in the Wedding in Cana, two formally similar compositions of 'three figures, represent the two poles of the art of that time. Rublov paints a vision elevated to the sphere of ideas — the unattainable mystery of the Eucharist. The Kalenić artist paints the wedding of an angel-like young couple, ennobled by the symbols of sacrifice land blood bonds, abandoning himself to a piety which is too free, almost sinful. Each line of Rublov's majestic figures radiates power and mystery. The Serbian firesco is an apotheosis of the earthly happiness of lovers. The strange lyrical sense of tragic times flourishes in Serbian literature in the same period as the paintings of Kalenić. The Poem of Love by the Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarević is the nearest counterpart to the Kalenić Bride and Bridegroom. Recited in front of their picture, The Poem of Love would sound like speaking with them.

Belgrade 1964