Sensitivity and grace in fifteenth-century Serbia

ANCIENT Serbian art began to flourish towards the end of the twelfth century, but went into decline after 1459, when Turkish invaders occupied the fortress-town of Smederevo, the capital of the Serbian Tsars. Nevertheless, this national art survived, under the Ottoman yoke, until the first decades of the eighteenth century. When the Turks finally retreated from the Danube basin, Serbian artists were ready to make their contribution to the late Baroque period of central r and western Europe.

Against the background of the turbulent history of the eastern Mediterranean region, the Balkan peninsula and the Danube basin, Serbian art, which had formed an integral element of Byzantine culture, followed its own path of development.

When the great Serbian Empire crumbled after the disastrous battle of the Maritza, in 1371, and the extinction of the Nemanja dynasty, the princely families of the Lazarevići and the Brakovići struggled to retain their hold in the narrow territory that stretched from the belt of land between the Danube and the Save in the north to the two Morass in the south (these two tributaries, which flow northward from the Macedonian border to meet in a single river that joins the Danube east of Belgrade, should not be confused with the Morava of Czechoslovakia, from which the vast region of Moravia takes its name).

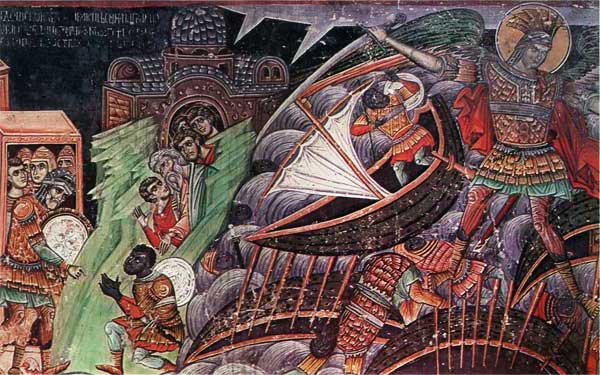

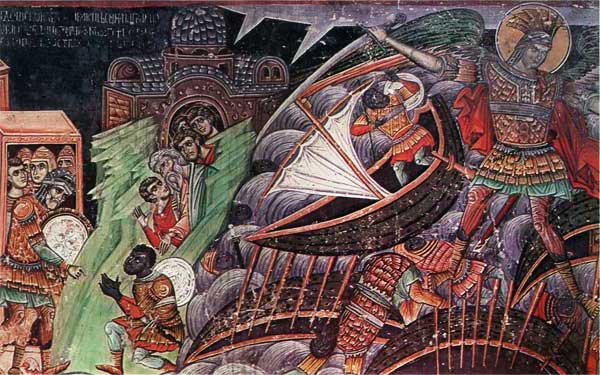

Detail from a 14th-century fresco known as "The Saracens", from the Church of St. Archangel, at Lesnovo.

It was here that the Serbian "despotate" (a term borrowed from the Byzantine hierarchy of government, and in no sense pejorative) had a short-lived existence between 1402 and 1459, as the last outpost of free Christianity in the Islam-dominated Balkans. In the struggle between the Christians and the Ottomans, this little Serbia of the south became the refuge of countless emigrants from Byzantium, Mount Athos, Macedonia, Bulgaria and Albania.

The roads leading to the despotate were crowded with refugees: princes chased from their principalities, bishops deprived of their bishoprics, monks without monasteries and seigneurs who had lost their fiefs and castles. In their train followed a motley retinue of writers, architects, painters, musicians and singers—the whole constellation of artists that surrounded the rich and powerful figures of the day.

Stephen Lazarević, son of Prince Lazar who fell in battle in 1389 at Kosovo-Polje, where the Turks finally established their supremacy over the Serbs, was a typical representative of his age. Bearing the title of "despot", conferred on him by the Byzantine Emperor, liegeman of the king of Hungary, vassal of the Sultan and commander-in-chief of his own army, warrior and patron of letters and himself a poet, he attracted scores of writers to his court at Belgrade. Sycophantic contemporaries called him "the new Ptolemy". He was the founder of the Resava school (so-called after the monastery that stood close to the river of that name). This was not merely a school of copyists, as has sometimes been slightingly suggested, but, as it was referred to at the time, of "translators".

Contemporaneous with the Resava school, and created under the same auspices, was a still more significant school. It

has sometimes been said that art is the product of peaceful and happy times; the Morava school, as it is called by historians of Serbian art, which served as a nursery of sensitivity and grace during a dark, doom-laden period, provides ample evidence that nothing could be further from the truth.

From the twelfth century onwards, the quest for the aesthetic followed two paths with artists seeking both outward and inner beauty. These two contrasting and unevenly balanced trends, the point and counterpoint of which are most apparent in architecture, reached their apogee during the years of the despotate.

The miniature of St. Luke, with a bull by the master-painter Radoslav come from a New Testament dating from 1429, now in the Saltykov-Shchedrin Public Library, Leningrad.

The churches of the Morava school, whose inner volumes were perfectly planned, and whose facades were covered with sumptuous decoration, were suited both to the routine of daily offices and to the occasional splendour of great ceremonies. Their floor plan took the form of rectangles with semi-circular ends, above which soared the great conches of the apses and the crowns of their domes. Their whole structure was adapted to the requirements of a complex liturgy involving numerous clergy, two choirs, and the spectacular processions depicted in contemporary frescoes. All the different sections, passages and partitions were functional and acoustically perfect.

The vocal music which completed the beauty of these churches has only recently been rediscovered. In fact it was not until after the Second World War that Serbian manuscripts dating from the turn of the fourteenth-fifteenth centuries and containing musical notations were deciphered and their notes transcribed. Two of the processions which appear frequently in ancient paintings—the "Grand entrance" and the "Communion of the Apostles"—can now be accompanied not only by the words, which were already known, but also by the authentic musical background which gives to the gestures of the depicted characters a strange, unfathomable, almost unearthly rhythm, a music which inspires in its listeners the sentiment of unshaken and unshakeable belief.

The earliest frescoes, painted in the mid-fourteenth century, portrayed the unusual figures of the "chapel-masters" in their richly decorated robes and strange, white, three-cornered hats. Now we not only know their names —Stefan, Isaija and Joakim—but also the music they composed .

The beauty of these hallowed, music-haunted places was enriched by a new style of wall painting, in frescoes which capture the same subtle and musical delicacy of tone and from which powerful and severe brushstrokes are entirely absent. The human portraits they contain are stylized, plastic, almost sculptural; like the music, the figures seem unearthly.

From this point onwards, the painters of the Morava school abandoned the techniques employed for earlier frescoes in favour of the more subtle approach used for painting on wood. Attitudes and movements are captured and, as it were, frozen for all time; yet the gestures remain gentle and harmonious. In the paintings of the Serbian despotate, scenes from Christ's life on earth are favorite themes: warrior–saints, monks, bishops and preachers alike are represented as "celestial men and terrestrial angels", glowing with outward beauty and inner perfection, inhabitants of a universe whose only dimensions were pictorial, literary and musical.

The miniature of St. Mark with a lion, by the master-painter Radoslav come from a New Testament dating from 1429,

now in the Saltykov-Shchedrin Public Library, Leningrad.

This art is a faithful reflection of the mysticism of Eastern Christianity. There is something dramatic in the artistic expression of the wonder provoked by revelation. The sanctuary of the church, the "holy of holies", is hidden behind a partition to which icons are attached, the iconostasis which, like the scenae frons of ancient theatres, contains three doors draped with rich fabrics. At certain specific moments in the rituals, these curtains are raised. The larger churches were decorated with rich polychrome stone facings: broad ornamental bands, arcades and large, rose-shaped designs, and figures executed in low relief, especially around the windows. There was a great variety of decorative motifs: scrollwork, angels, mythical animals and enigmatic shapes, among which, at the Kalenić monastery, for example, stood the centaur Chiron, who taught music to the Greek hero Achilles.

HE ancient dichotomy of outer and inner beauty is a recurrent feature of works of the Morava school, revealed in its architecture, its frescoes, its icons, its rich brocades, its jewellery and above all its miniature paintings. Invariably the ornamentation expressed an outer beauty behind which transcendent, mysterious, barely perceptible values lay concealed.

This grandiose vision of a perfect world, evoked during an age of utmost peril, exercised a profound attraction on the survivors of Christian Byzantium; for the mystics and intellectuals who, during the fifteenth century, wandered between Italy and the distant Russian steppes, it had the value of a prophecy.

The merit of this fifteenth-century art, which emerged from a Serbia whose frontiers had been so reduced, which was both lordly and monastic and which was the product of luxury and asceticism alike, was that it reconciled the outer with the inner beauty. European art was at a crossroads: while the West turned its back on medieval thought and art, the East continued to cling to them tenaciously, adopting a sceptical attitude both towards matter, nature and the power of human reason, and towards the spirituality of antiquity from which, nevertheless, it derived its art—an art in which form alone resembled reality, yet was itself a symbol and an allegory. The figures of the writers embraced by the Muses in the miniatures of the master painter Radoslav are perhaps the finest examples of this complex, traditionalist culture, which found its most perfect expression in the art of painting.

In: The Unesco Courier. 31 (august - september 1978) 41-42.