When, in 1881, Arthur Evans saw the fresco of the angel on Christ's sepulcher in the monastery of Mileševo, he had the impression that he was standing before a vision. In a remote mountainous area in the northwestern part of the former Turkish Empire, and in a church surrounded by ruins, he was struck by two peculiarities. One was the appearance of an art, fresh yet experienced, in an environment noted for its wilderness and almost total insecurity. The other peculiarity was the date. How was it possible that in 1240 a.d., at a time when in Italy, the classical land of fresco painting, the design of the human body in the monumental paintings was still restricted by rigid medieval forms, an art appeared in medieval Serbia which was so close to the beauty of the wall paintings of antiquity? With a feeling of uncertainty, Evans raised the question whether the earliest beginnings of the Renaissance took place in the Balkans.

Fresco of the angel on Christ's sepulcher in the monastery of Mileševo, around 1235.

Recent examination of monuments of Byzantine art has shown what a lively pulse that ancient international art had. The early architecture of the Bulgarian Empire of Simeon in the beginning of the tenth century, the monumental art of Macedonia in the second half of the eleventh century, and the austere art of the Serbs in the beginning of the thirteenth century show finished and well-defined styles, without the naive uncertainties of inexperienced searchings. The Slavic art in the Balkans was created and developed during periods of conflict and in dangerous places, beside ruined palaces of former rulers and along fortified Byzantine military roads; and the road from Salonika in the south to Belgrade in the north remained for centuries an important artery traversed by leading artists of this area.

The oldest surviving great medieval paintings in present-day Yugoslavia are in Ohrid. They date from the second half of the eleventh century. In the restrained coloration, dominated by blue, white, and ocher hues, the solid contours of boldly drawn figures interpret scenes from the Old and New Testaments as well as learned theological speculations. Great formats of figures, firm rhythm, and simple symmetry of composition have been spontaneously woven into the bulky shapes of internal architecture. The architecture and the frescoes interpenetrate one another. The frescoes inside the church of St. Sophia in Ohrid do not decorate surfaces; they fortify and animate the strength of the wall, and at the same time reveal the symbolic values of individual spaces.

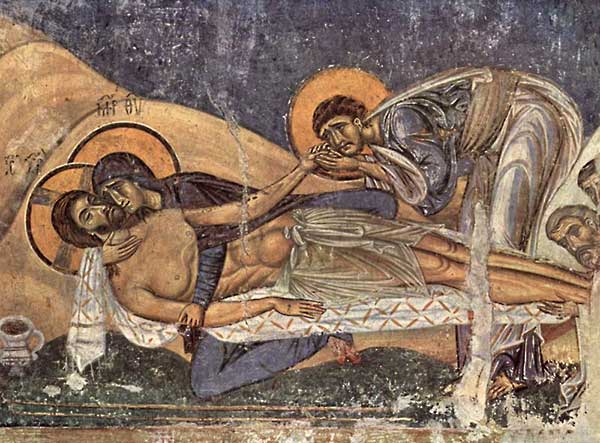

Paintings in the Macedonian churches from the second half of the twelfth century, a century later than those in Ohrid, display quite opposite characteristics. The well-known frescoes from about 1164 in the church of St. Panteleimon in the village of Nerezi, near Skoplje, and the recently cleaned frescoes from 1191 in the church of St. George in the village of Kurbinovo demonstrate all the qualities of a lively and highly decorative narrative style, in which every stroke overflows into an excessively stylized and calligraphically sharp arabesque.

The Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi, Pieta (XII century)

This quality and style of painting, highly effective and full of virtuosity, spread to the north along the Byzantine military road to the town of Niš, the Naissus of antiquity. Stephen Nemanya, the founder of the most renowned dynasty of medieval Serbia, was able to compete with the Byzantine high officials at Skoplje and Niš; and by the closing years of the twelfth century Nemanya built in those towns (at the time, still Byzantine) churches in which Greek artists painted frescoes in a style identical with the style of frescoes at Nerezi. This artistic development, however, left no traces in the interior districts of Serbia. The refined art of the late period of the Comnenian dynasty in Byzantium depicted personalities from the Holy Scriptures as tenderly reared courtiers of Constantinople, excessively carefully clad, with perfect hair-dress and too polished manners. The Serbs of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries were apparently not attracted by scenes from the life of Christ and from the lives of saints in which the countenances and costumes reflected the decorum of high society in Constantinople. And after the fall of Constantinople in 1204, new political and artistic trends started to form in Nicaea, and these were better suited to the young Serbian society.

The political and cultural developments of the Serbs in the beginning of the thirteenth century did not go hand in hand. While the Serbs did profit by the collapse of Byzantine power, they did not depart from Greek Orthodoxy, and they did not abandon the art which they had created according to Byzantine models. Quite wisely, the Serbs maintained rather lively political and ecclesiastical relations with the not too dangerous Nicene Empire, and they succeeded in obtaining from Emperor Theodore Lascaris formal recognition of Serbian political and ecclesiastical independence. This new relationship with Byzantium influenced powerfully the artistic life of medieval Serbia. Thus, the Serbs established friendly contacts with Nicaea at a time when a renaissance was taking place at the Byzantine court on the soil of Asia Minor.

What happened in the course of the first few decades of the thirteenth century in Serbia is truly a miracle: in an environment largely given over to shepherding, the indigenous painters, after receiving a few lessons from Greek artists, themselves became interpreters of a newly awakened classical art, to which they devoted all the powers of their lively temperament. By 1260 the artisans of the third generation of the Nemanya dynasty found themselves masters of classical forms. The road to the summit was marked by two great monuments — frescoes in the churches of the monasteries of Mileševo and Sopoćani. As is usual in the fortunate epochs of the history of art, the years of searching and of ascent produced more interesting, fresher, and more powerful painting than the times of the summation of the final results. While still uneven in expression, the frescoes of Mileševo flare with lively colors of spring flowers, of fresh grass and moist soil. In previous times, the luxurious colors were still more brilliant. The artists of Serbian Kings painted their frescoes with a special technique. The whole mortar background, which was first dyed with a lively ocher, was subsequently covered with thin sheets of gold. Centuries-old bucolic themes of paintings from antiquity were restored to a new life and transfigured in this small country of warriors and shepherds. The Serbian artists of King Vladislav were struck with wonder by the direct likeness between the old paintings and the living beauty around them. They painted frescoes at Mileševo with the redness of the Mileševo soil, with the greenness of the monastery's orchards, and with the whiteness of the snow on mountains leaning over the cupola of the tall church. From their paintings the living antiquity of the Balkans speaks, as interpreted by the awakened talents of the recent barbarians living next to the Hellenes. These "hated northern neighbors," whether ancient Macedonians, Thracians, or Slavs, when drawn into the magic circle of Hellenic culture matured quickly and made themselves a part of the body of classical art.

The frescoes of the painters of Mileševo impress us not only with the details of classical treatment of the beauty of faces, but with nobility of proportions and skill of composition. This painting fascinates us, above all, by its tremendous scope and power. Each scene taken alone as a figural composition is surprising in the breadth of its conception. Yet these great themes, painted within thin red frames, are also subordinated to a still larger entirety, to the general idea of the whole painted space.

The painted decoration of the nave of Mileševo has been heavily damaged in the course of centuries and is preserved only in a fragmentary state. However, even from these fragments one may obtain an idea of the great art of the lively colored surfaces, in which the wholeness of the painting could be observed only if one moved about the church. The function of the wall in that entirety has been completely neglected; the wall serves only as a neutral carrier of a great chromatic symphony, in which a rich and softly modulated color dominates. The massive structure of the painting in Mileševo has been achieved spontaneously, without any aspirations toward a rhythmical order and symmetry; there is a very free and often surprising use of effective accents which cross one another through the space, thus forming the volume and surface of the internal architecture into an imaginary, endless area, completely imbued with the golden atmosphere radiating from the frescoes.

The silent, harmonized, and quiet solemnity of the Mileševo paintings is striking for its modesty and essentially human beauty. The artists of Mileševo were only occasionally inspired by the paintings of a monumental character; they certainly must have known the old mosaics of Salonika, yet they kept their eyes more often on models to be found in the painting of miniatures. They were not interested in the classical sculpture of antiquity. Their strongly coloristic classicism is a direct descendant of that precious painting which was best preserved in Byzantium in the richly illuminated manuscripts.

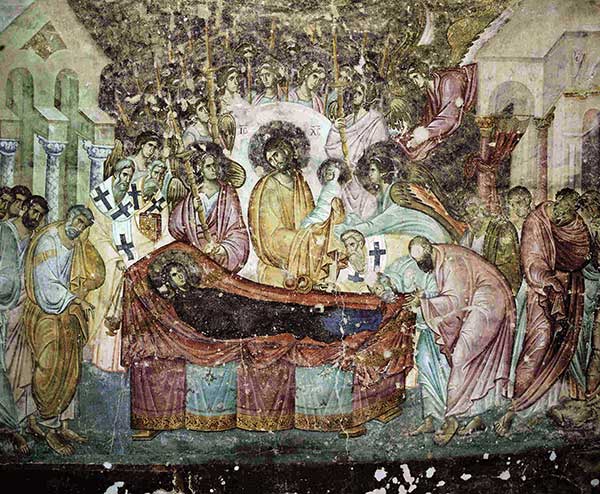

The slightly later frescoes of Sopoćani, from about 1260, testify that the classical style of Byzantine wall painting in the middle of the thirteenth century had changed considerably. The frescoes of Sopoćani differ greatly from those of Mileševo. While Mileševo is attractive for its freshness, Sopoćani is imposing because of its maturity. That contrast embraces essentially the entire history of Byzantine classical monumental style in the period of the Latin Empire.

Older surveys of the history of Byzantine art often ended with the year 1204, explaining that whatever followed in the art of Constantinople was complete decadence. Only in the last few years has it been shown that in the Byzantine Empire, as in other parts of Europe, the periods of blossoming of the arts did not correspond to the periods of political power. The fact that the Byzantine court in Nicaea had turned its attention to the achievements of classical antiquity had no significance politically. Yet in the field of the arts that excursion into the glorious centuries of the past, undertaken at the beginning of the thirteenth century, was much more easily realized on Byzantine soil than it would have been in the West.

The frescoes at Sopoćani show quite precisely the height of the artistic traditions as well as the height of culture in the politically crumbled Byzantine world in about 1250 or 1260. The present-day admirer of art will note that classicism

cast a slight shadow on the frescoes of Sopoćani.

The painters of Sopoćani proved to be sovereign masters of great decorative paintings. If classicism means the harmonic balance of design, color, and plastic form, achieved with restraint, quiet, and a sense of proportion, then the painting of Sopoćani is completely classical. However, a certain complexity and an almost excessive perfection take away from the Sopoćani frescoes that brilliant splendor of directness.

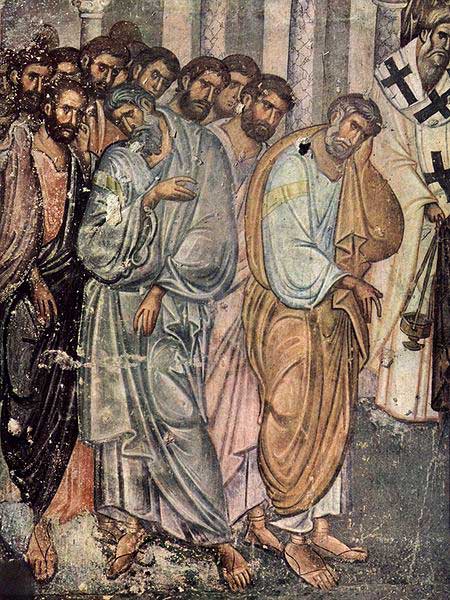

Sopoćani, Death of the Virgin Mary, detail: Grieving apostles, around 1262.

It would seem that, in their desire to define the human figure as precisely as possible, the young artists of Sopoćani used some hidden spotlights which make the great scenes, to a certain extent, theatrical. The spacious surfaces of the simple internal architecture of the Sopoćani church are covered with paintings which are powerful and well designed. That decoration is perfectly harmonized with the space, yet not in the same way as in the paintings of the thirties of the same century. In Mileševo, the predominant color — as if it were a soft fluid — floats vaguely on the internal walls of the church. The paintings of figures in Mileševo become indistinct in relation to the space, tend to go over into the real space in front of them. At Sopoćani, the boundary between the real and the imaginary is drawn logically, with a certain sense of measure characteristic of classical painting.

The frescoes at Sopoćani demand distance for viewing. The serious, beautiful, and athletically developed figures in the Sopoćani frescoes live the lives of chosen dwellers on the Christian Olympus. The enormously large fresco representing the death of the Virgin, on the western wall of the nave, certainly belongs to the most grandiose works of wall painting of all time. Everything in it has been arranged by a sure and experienced hand: the protagonists who interpret the solemn moment of the taking of the soul of the Virgin to heaven, and the choir of the distressed. The immense mass of persons present — apostles, bishops, women, a choir of angels — has been skillfully organized and distributed in accordance with the requirements of the whole painting. At some places this mass of persons appears subdued, while at other places it is accentuated.

This art which aspired with all of its powers to create an impression, to fascinate, often had to deprive itself of more intimate sentiments. The fine, rich modulation of color seen in Mileševo would have been out of place in the robust world of Sopoćani. The complicated problems of monumental composition, which were beyond the reach of the previous generation of artists, are completely mastered by the virtuosos of Sopoćani. However, tending toward new formulations of beauty, the new masters sacrificed consciously the old beauty, and that step was fatal for the future development of Byzantine wall painting.

In Sopoćani the forms were still painted and the painted spaces condensed into a firm context in a style which reminds one of the reliefs in antiquity; in that way a fresco still retains the value of a wall painting. Yet, once the curiosity about the problem of a figure in space was awakened, it remained throughout the later Byzantine painting.

This new concept of a picture in which space, light, a living plastic body, clear architectural forms, and landscape exist side by side attracted more and more Byzantine artists. Under the influence of these new tendencies, painting became steadily more convincing, closer to reality, yet at the same time less capable of adapting itself to the requirements and basic qualities of wall painting. Sopoćani thus stands as the summit and the end of the genuine monumental painting in medieval Serbia and Byzantium.

Sopoćani, Death of the Virgin Mary, around 1260

In that truly great moment of parting, the experienced artists of Sopoćani created a solemn finale, condensing in it values and experiences of a great style which could no longer be repeated or continued. Byzantine painting was returning to the form and to the rational, which could be expressed in paintings of a smaller size, as on the strictly limited surface of an icon. Yet the power of imagination in the early thirteenth century still lives in the frescoes at Sopoćani; their great creators relentlessly filled the spacious surfaces of the church. In fulfilling the commitment, however, these artists did not rely solely on the powers of a spontaneous creating force.

At first sight, and especially in photographic reproductions, the quiet classical style of the frescoes of Sopoćani appears much too measured and even unoriginal. A glance at these frescoes may remind one of the correct art of the ancient Roman reliefs: apostles resembling Romans in togas, angels resembling the winged victories, heads of old men resembling the portraits of philosophers of antiquity. The delicate relationship between antique forms and Christian context was often disturbed by some disproportion or misunderstanding; the artists of Sopoćani mastered completely the forms of the art of antiquity, yet they blended this art with their own Christian sensibilities and logic. There is also a certain scholastic logic, especially in their approach to the entirety of the painted decoration in Sopoćani. The forms and ideas are interdependent, and they mutually elevate one another.

This high degree of harmony may be noted particularly in the frescoes in the lowest tier of the altar space. There is a unity in the movements of a row of holy fathers with their heads inclined, achieved by the rhythm of lines only; yet that sense of unity is strengthened thematically as well. These old holy men, who appear as pilgrims marching toward Christ the Lamb, hold in their hands open parchment rolls inscribed with the text of a common prayer which flows continuously from one roll to the next. The magnificent harmony of the prayer, stories told epically, and sternly conducted liturgical festivities imbue the frescoes of Sopoćani with a convincing seriousness. In these frescoes an idea sublimes the forms and ennobles the faces, and beyond that boundary of solemn beauty one could go no further.

The next generation of painters, which was active in the last decades of the thirteenth century, was no longer able to repeat even approximately the clearly formulated style of the paintings in Sopoćani. Among the frescoes in the monastery of Gradac, one finds only occasionally an isolated powerful figure of some prophet copied from the walls of the Sopoćani church. All other spacious figural compositions reveal that a new style of painting had already started its conquest of the walls of the newly built churches. In the clearly separated scenes one detects novelties which were foreign to the old monumental style: deeper spaces, with little figures in lively movement; an ever larger landscape in the background; and more and more decorative buildings of fantastic architecture.

Historians of Byzantine art may engage in rather sharp polemics about the role of Nicaea and of Constantinople, about the beginnings of the austere style of the thirteenth century and the picturesque style of the fourteenth century. In the arguments, words will be used profusely to attempt to state what was expressible only through the pictures. Meanwhile, the wonderfully stern and powerful frescoes of Ohrid, of Mileševo, and of Sopoćani will continue to radiate for centuries to come an almost indestructible life, a life which mercilessly illuminates our ephemerality.

Translated by Miloš Velimirović.

In: The Atlantic (Boston). December (1962) pp. 101—104.